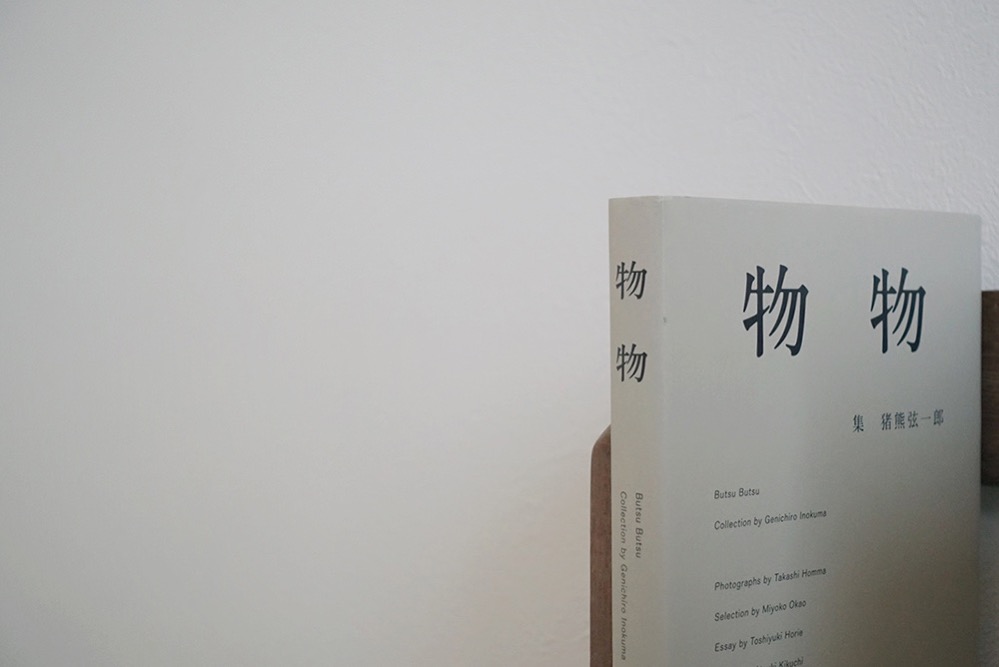

畫家猪熊弦一郎於二戰前曾於巴黎生活,戰後則去到紐約,不論在何處,他都會把偶然遇到的,與自己的品味相近的東西搜集起來,放在身邊,成為他日常生活與創作的養分。這些物品現在藏於日本丸龜市的猪熊弦一郎現代美術館之中,而《物物》可說就是這系列藏品的目錄。

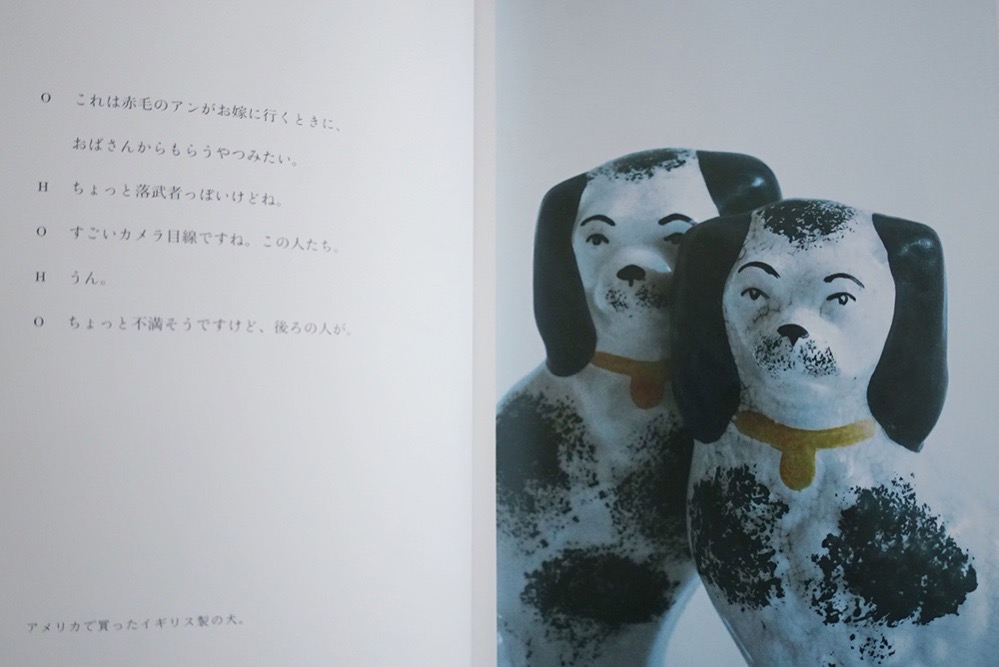

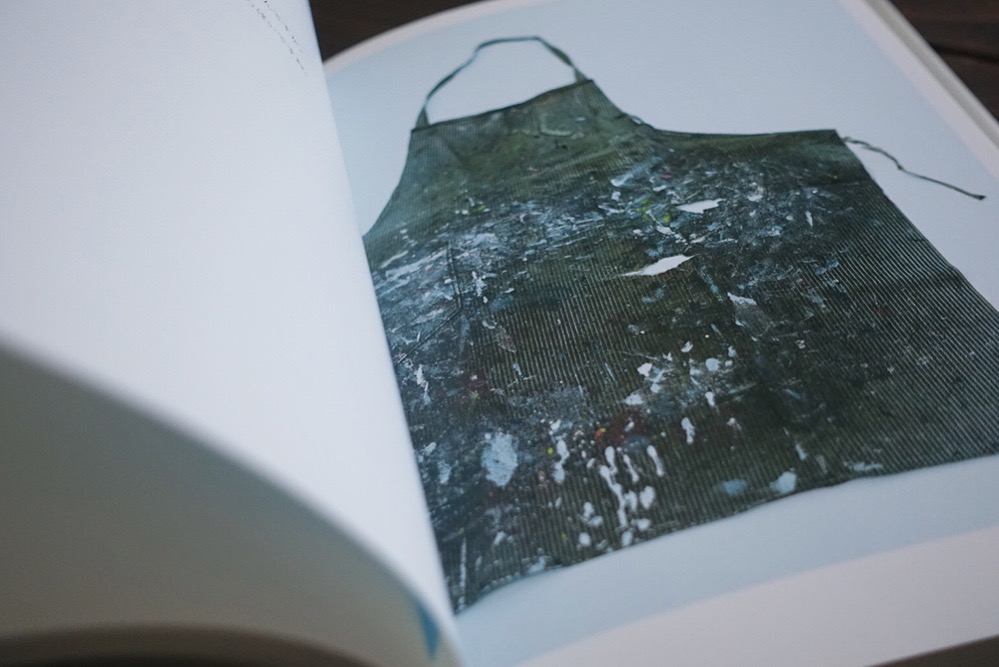

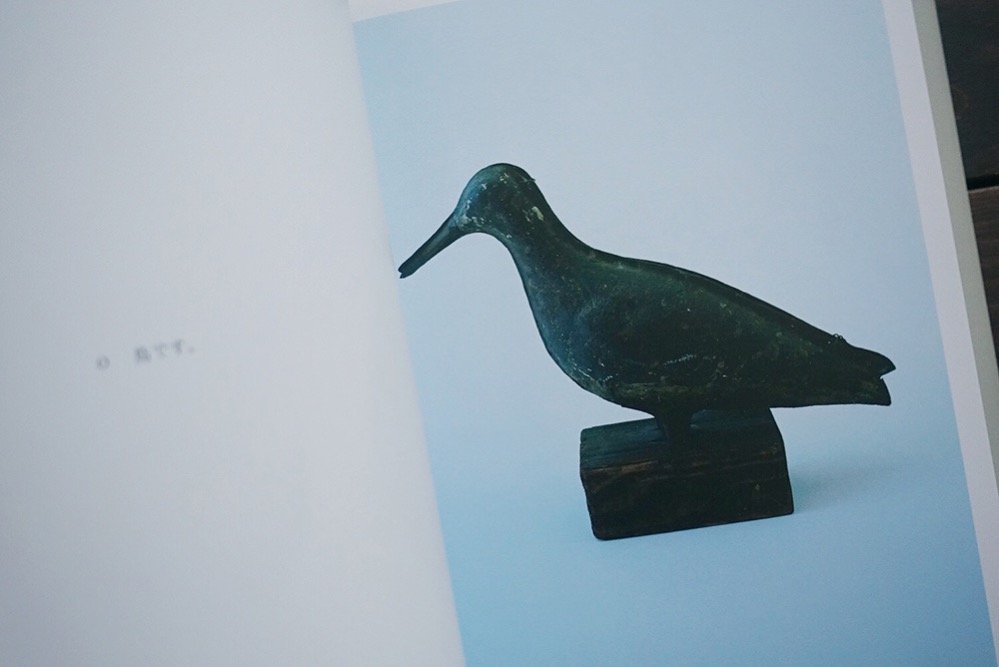

猪熊弦一郎的藏品範圍極廣極雜——鋸子、運送雞蛋用的木箱、剪刀、老舊的玩具,更多是根本無法命名的東西。書中沒有對藏品下任何解說,也沒有嚐試探研當中的歷史,只有攝影師Homma Takashi,以及造型師的岡尾美代子在拍攝時的簡單對話,例如:

一、

岡:呀,我懂了!是把完全沒關係的物品放在一起呢。

二、

岡:釘書機。

H:兔子釘書機。岡:是呢。

三、

岡:上面的手寫字很可愛呢。

H:很可愛呢。

看似沒有意義,卻將他們與物件相遇時最直接的情緒表現出來。

Japanese Artist Genichiro Inokuma resided in Paris before the Second World War, and moved to New York after it was over. He has a habit of collecting objects that charm him from places where he resides. Being surrounded by these objects provides nourishments to his daily life and creativity. The objects are currently kept in the Marugame Genichiro-Inokuma Museum of Contemporary Art, with Butsu Butsu being the catalogue of his collection.

Inokuma has a hugely diversified collection that includes a saw, a crate for transporting eggs, scissors, and some old toys. It is almost impossible to categorise his collection items. It is not the attempt of the book to elaborate the use or the history of the objects; all that is written are only simple dialogues between Homma Takashi, the photographer, and Miyoko Okao, the stylist, during the shooting. For instance:

1.

Okao: Oh, I got it! The idea is to place irrelevant objects side by side.

2.

Okao: Stapler.

Takashi: Rabbit stapler.

Okao: Indeed.

3.

Okao: The handwriting is cute.

Takashi: It’s cute indeed.

It may appear trivial at the first glance, but the dialogues are precisely their impulsive reaction when encountering the objects.

「以實用為目的的物件,某天突然變得無用了,一下子與理所當然的用途脫離關係時,就會向我們展示純粹物質性的表情。」工藝家三谷龍二在《生活工藝的時代》一書中,以這樣的開場白來介紹一疊和服店的價錢牌,這翻話也正好解析了《物物》一書吸引我之處。書中的物件自過去來到不屬於它們的年代,同時自其原來的意義解放出來,我們總算看到它們作為物件,最單純、最根本的美感。時代令物品失去了功能價值,卻將其美感解放出來了。

In the preface of his book The Era of Craft for Everyday Life, the artisan Ryuji Mitani interprets a stack of price tags from kimono shop by saying, ‘When the supposedly practical objects suddenly turn dysfunctional, and become dissociated from its original purpose, they begin to present to us an absolute materiality’. That can also explain how Butsu Butsu aroused my interest. Moving from their own era to the present where they misfit, the objects are liberated from their original purpose; we can therefore finally treat them as objects with the purest fundamental aesthetics.

The utility value of an object is lost along with the changing of eras, but its intrinsic aesthetics is in turn unleashed.