2018年9月,飛燕吹襲關西,淹掉国際空港時,我人正好在大阪,每日都在旅館旁一家咖啡店消磨時間。陰暗的店內只有一個中年男人,他把咖啡杯放在桌上,便會回到自己的位置讀報。我喜歡他的沉默,像船上的水手,一句多餘的話也沒有。

接近晚飯的時間,風愈來愈大,窗外傳來鐵皮抖動的聲音,一隻黑貓從後門走進來。男人熟練地為牠準備毛巾、水和貓餅。在嚴肅的臉容下,一定隱藏了激烈的情感吧,我忽然想,大叔的愛,真是複雜難解的東西。

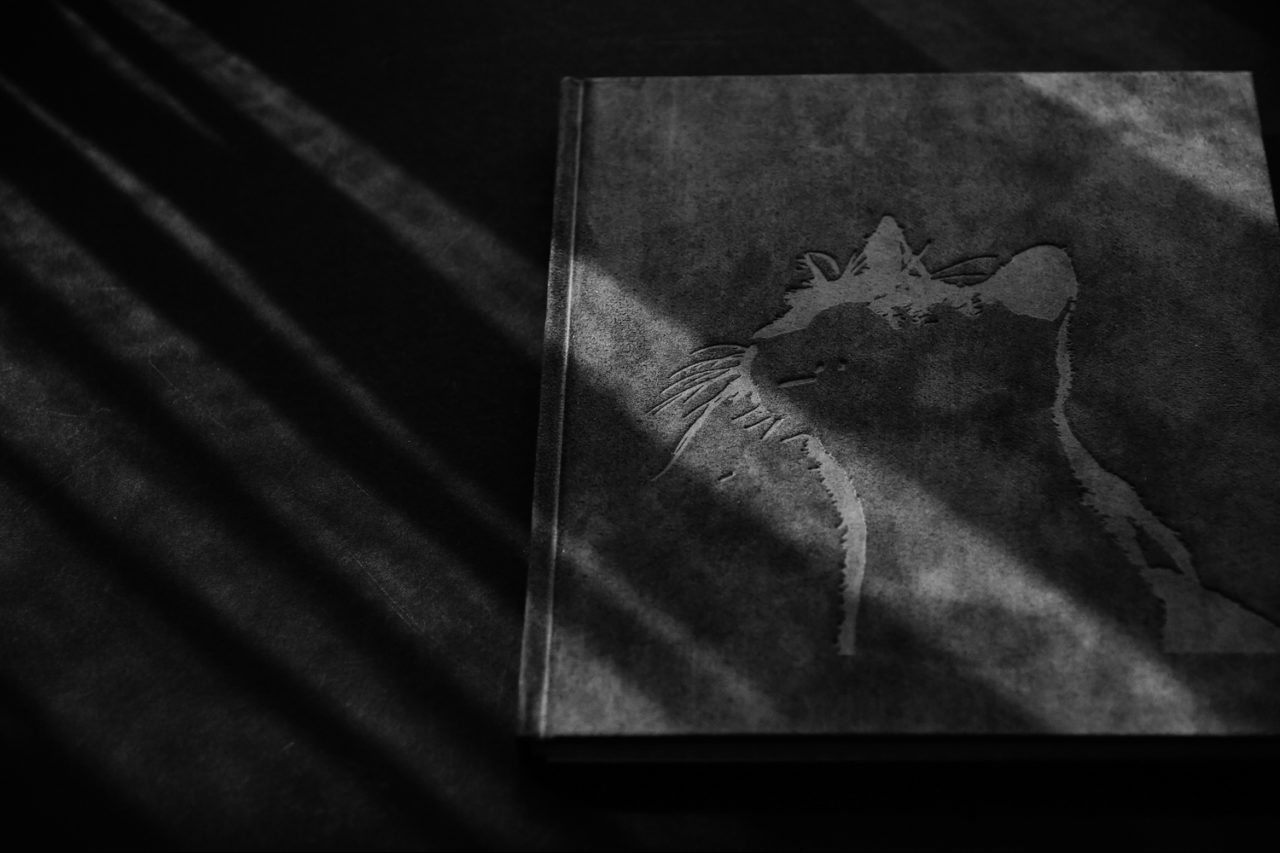

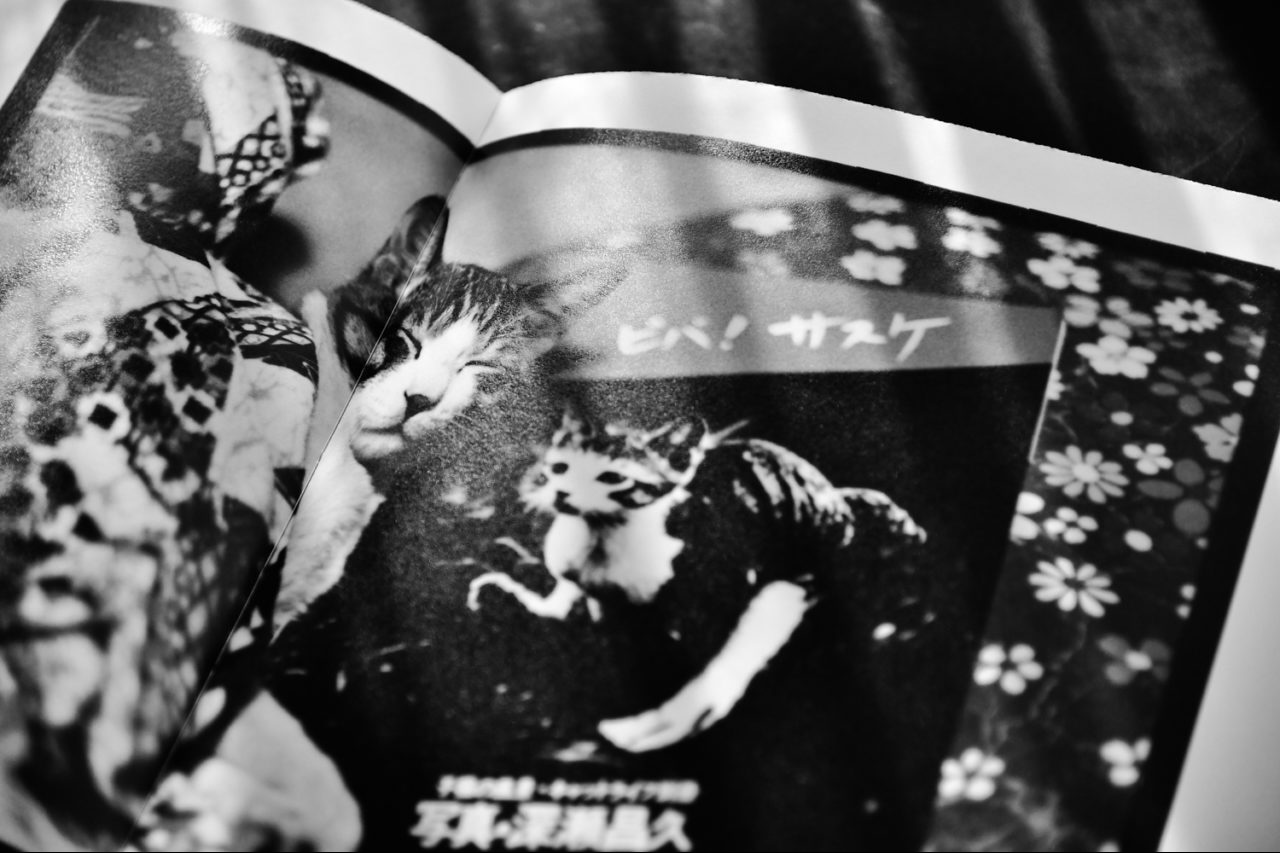

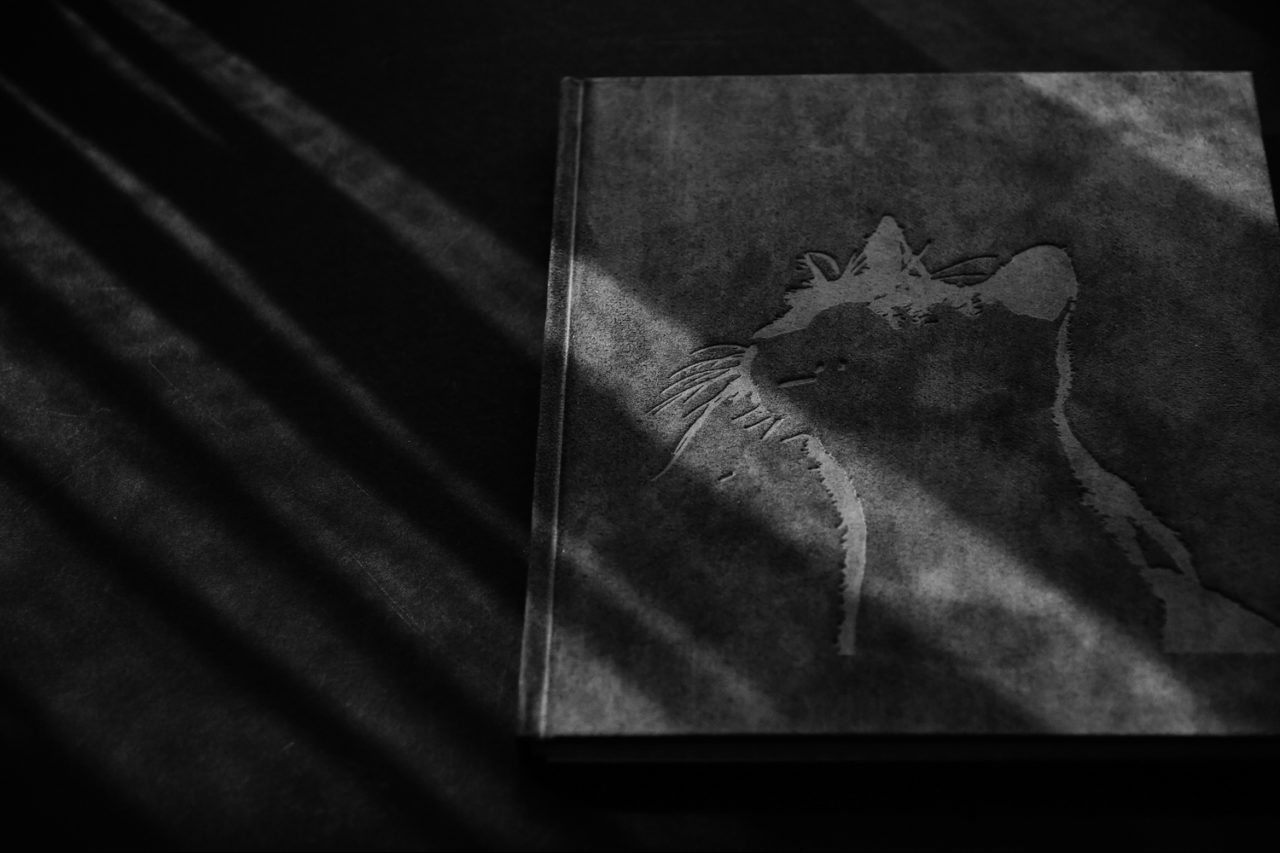

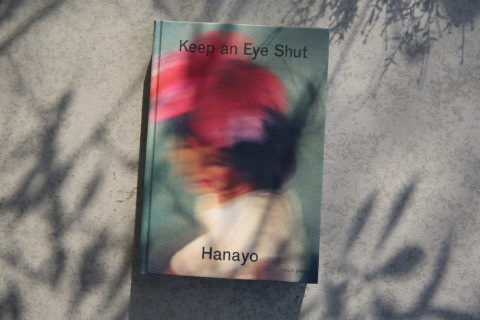

曾經有幾位朋友問我,最喜歡的攝影集是哪一本。我都不會馬上回答,而是講一個男人的故事。沉默的男人在妻子離開他後,決定養一隻貓,取名サスケ(Sasuke)。10日後,貓逃走了,男人急得四處張貼尋貓告示。過了2星期,鄰居帶了一隻貓上門。一看,雖然很像,但不是同一隻。那刻他想:「沒辦法,就當作是牠吧。」就這樣將牠領回,取名為サスケ二代目。無論去什麼地方,男人都會把貓帶在身邊,拍下各種照片。

這位大叔,名字是深瀨昌久。

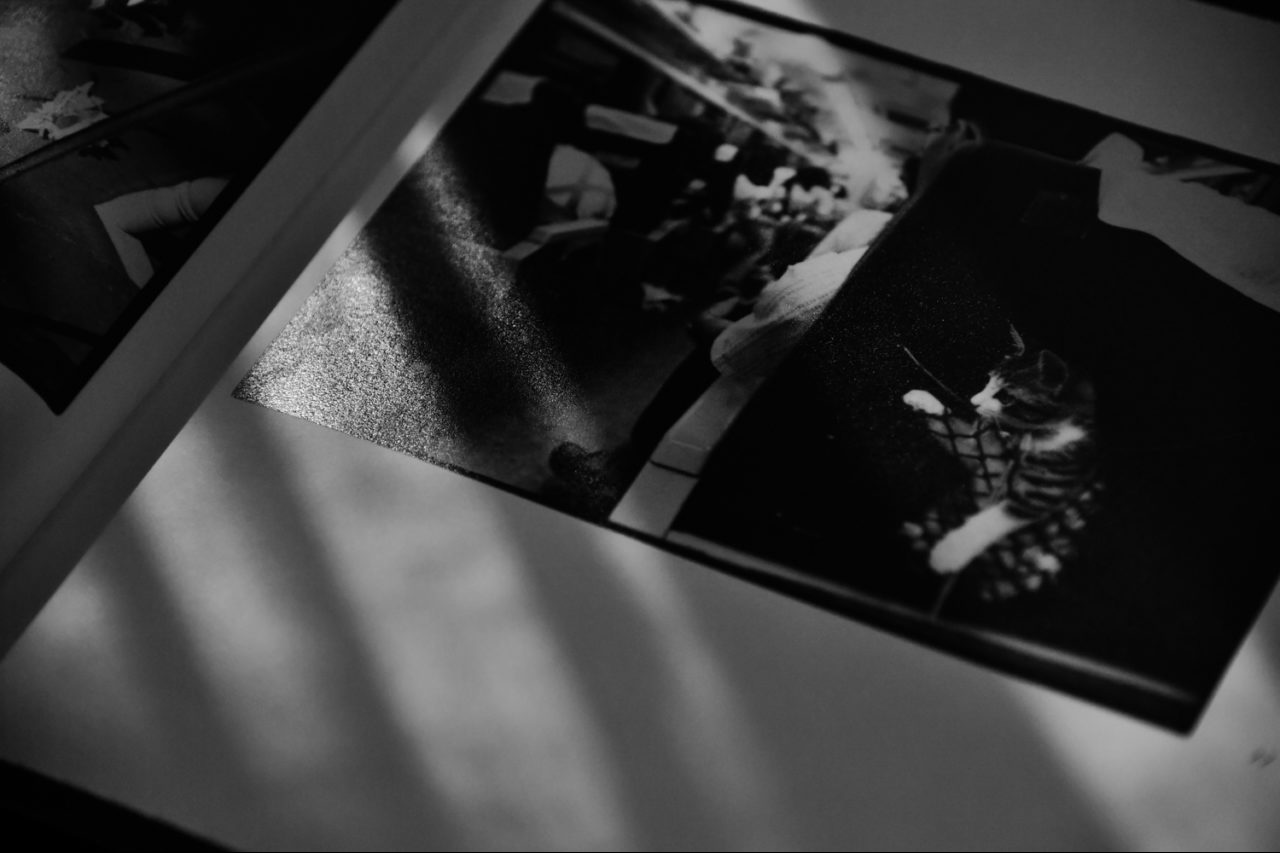

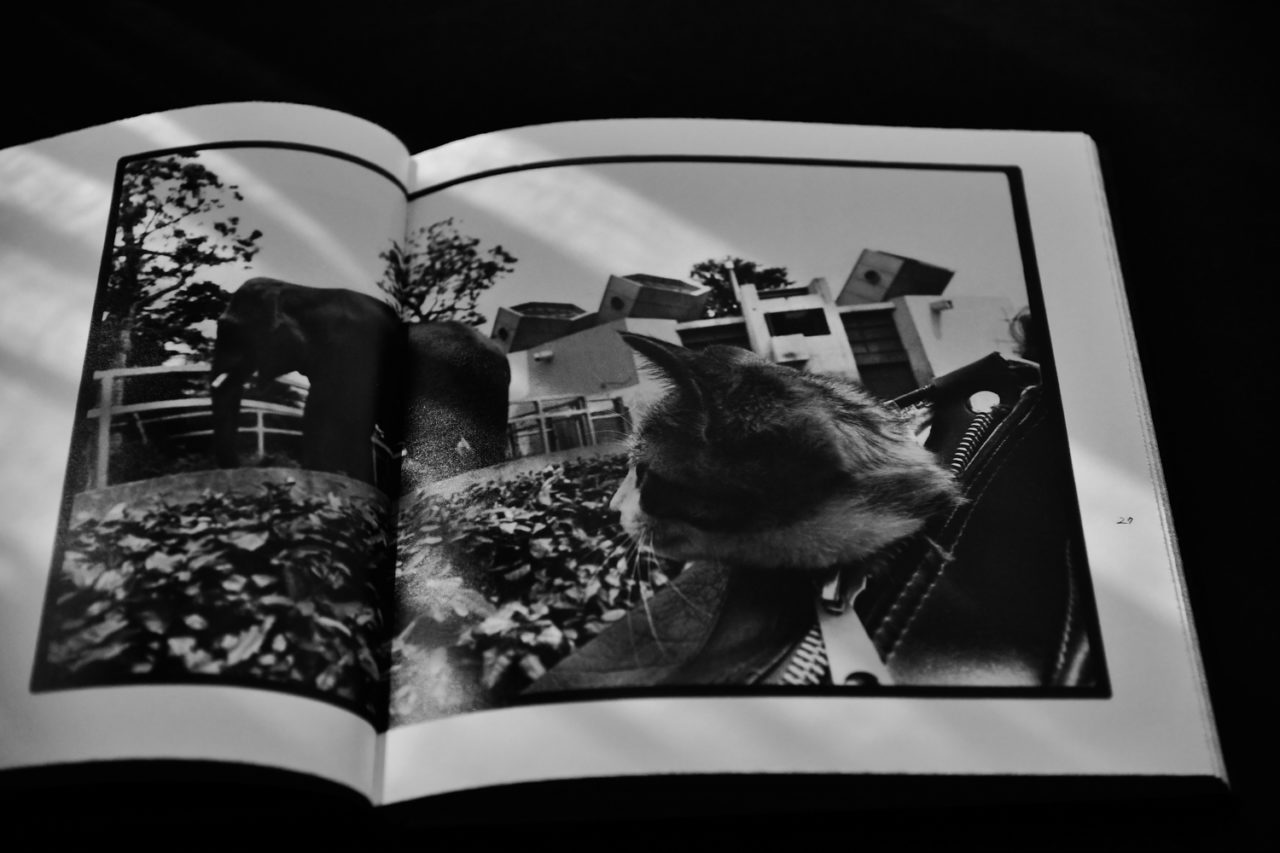

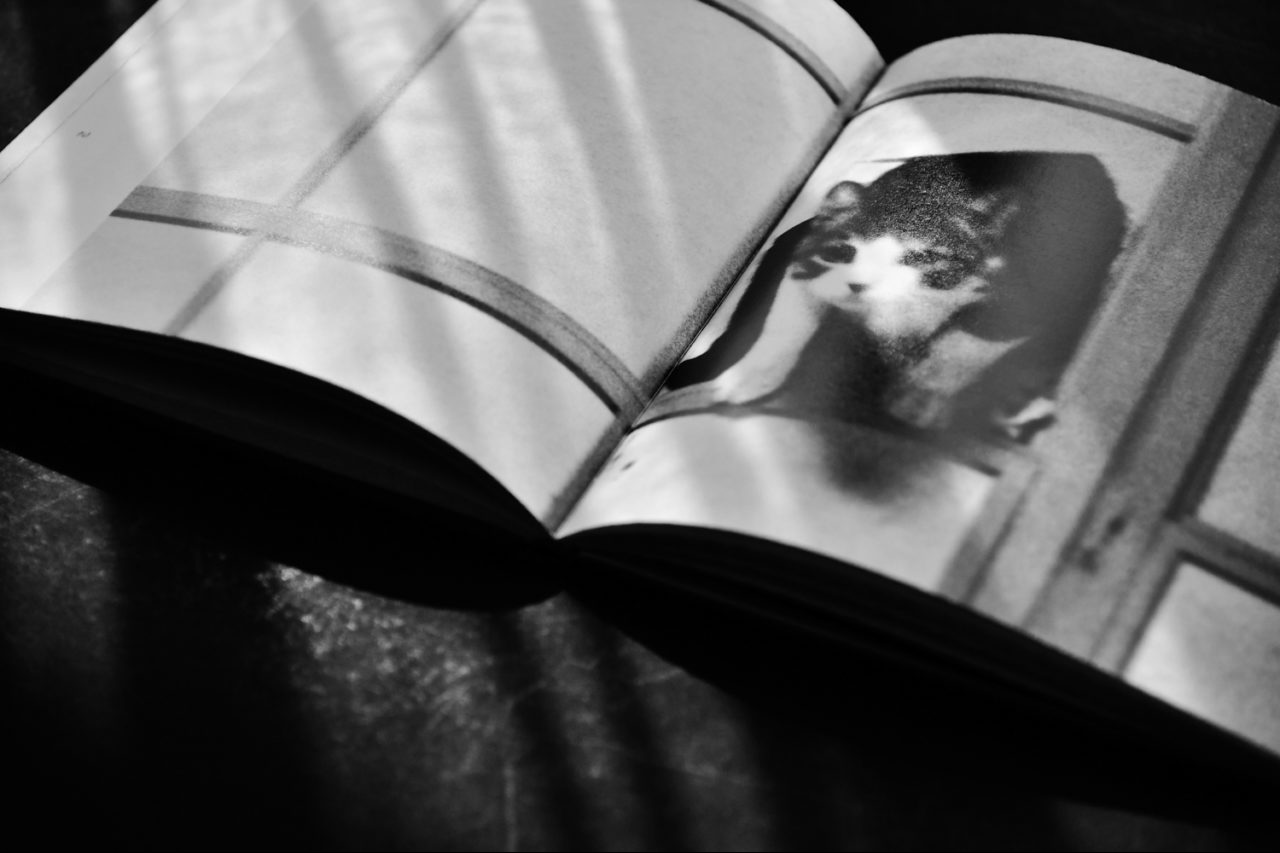

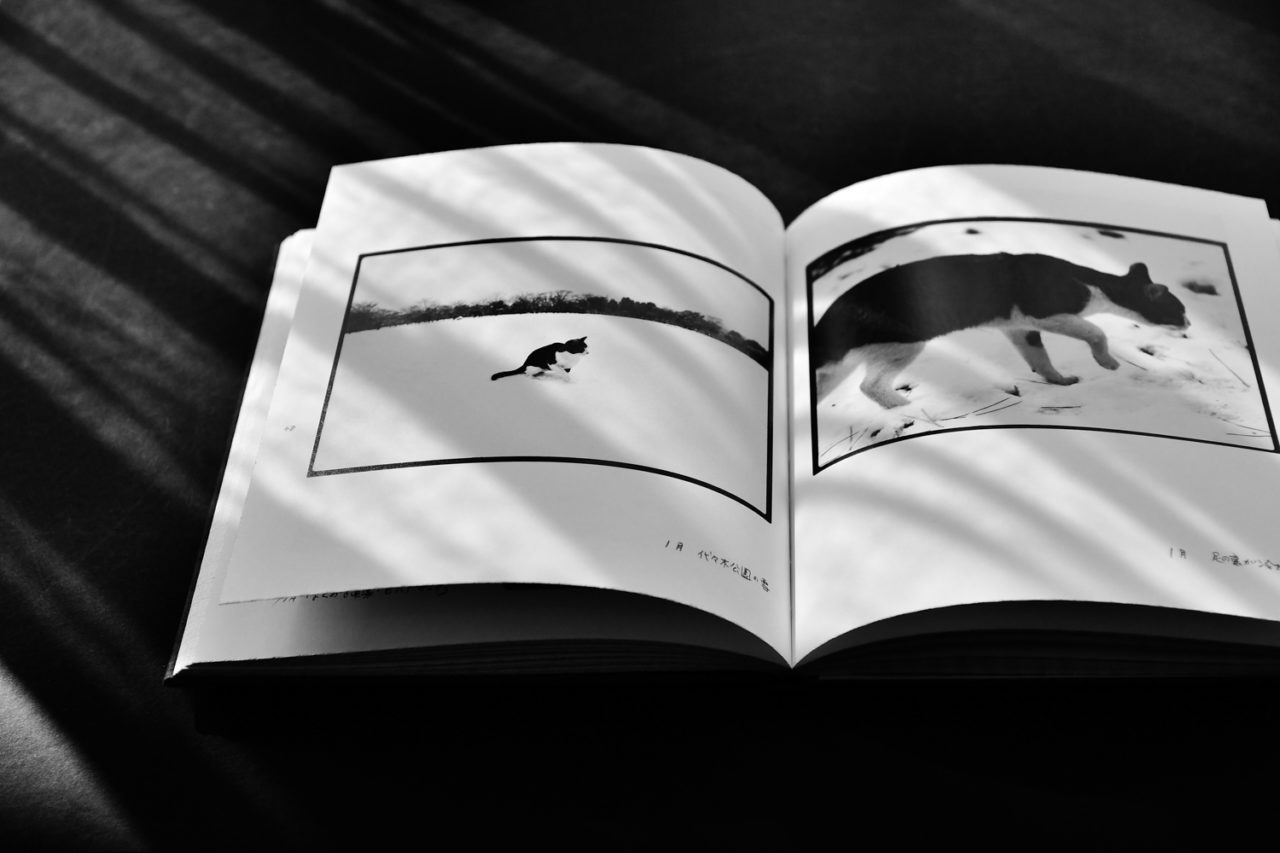

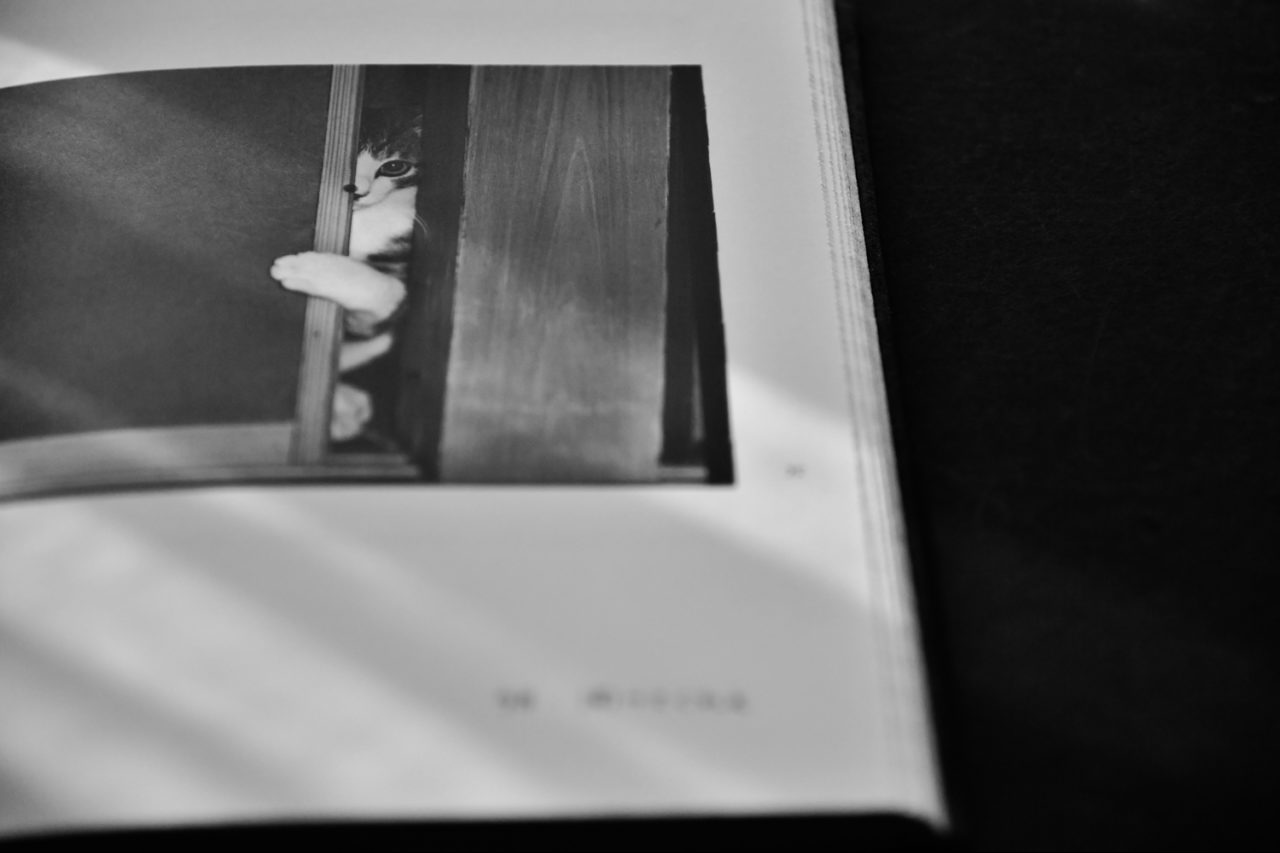

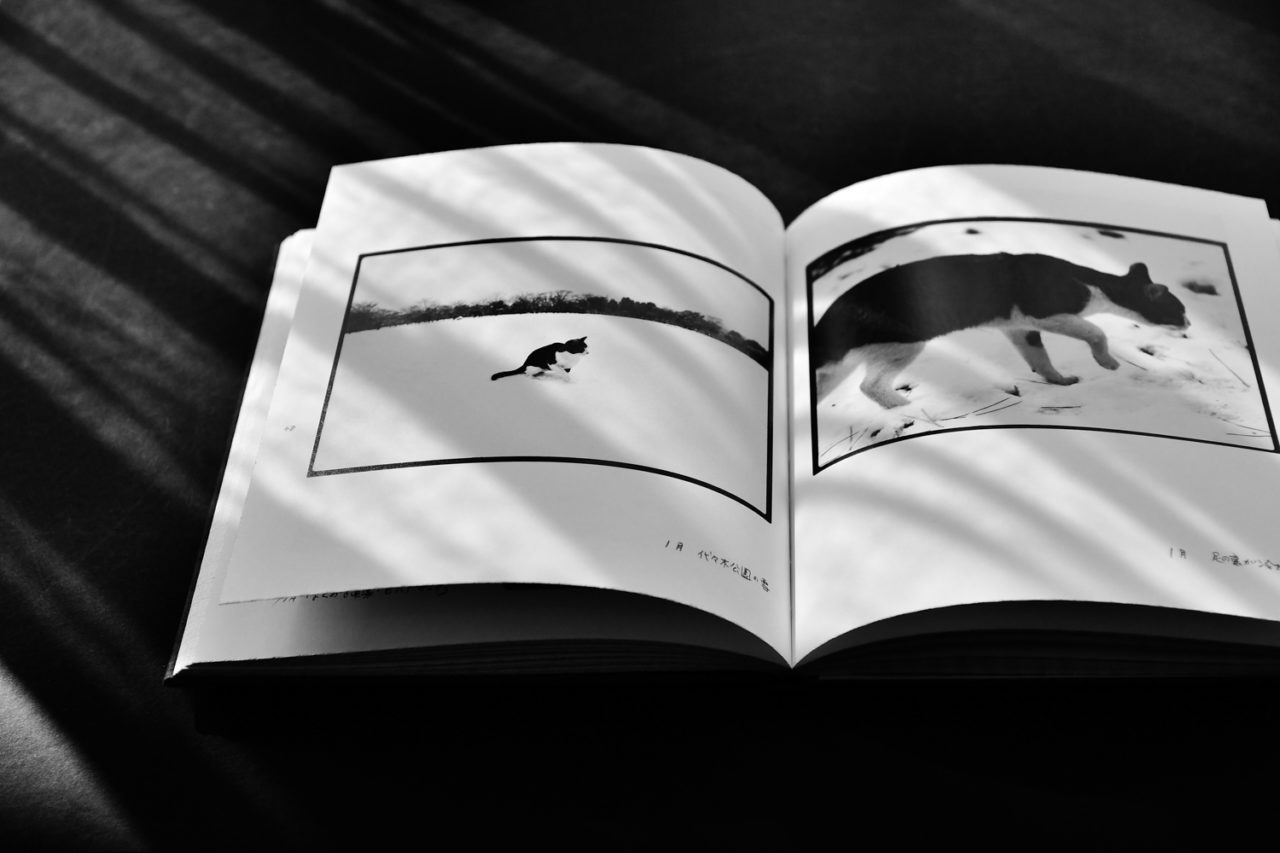

往後一年,深瀨帶著サスケ二代目到外面的世界。夏天的時候,他帶貓到戶外享受猛烈的太陽,到上野動物園看大象;初秋,他們到了大磯的海邊看海;冬日,冒著寒冷到代代木公園玩雪。照片下方,他以幼嫩的文字寫下各種生活的紀錄:「8月:初次爬樹」、「8月:初次跳過小河」、「1月:新年的雪」。深瀨回憶起這一年,他說:「我大部份時間都爬在地上,從貓的視線拍著照片,某程度上,我也成為了一隻貓吧。簡直是最快樂的事情,拍著照,和喜歡我的貓玩樂,感受到一年四季的和諧。」

每次打開深瀨昌久的《鴉》,我都會一口氣讀完。但每次看到他拍的サスケ二代目,很容易心情變得沉重,不願意再讀下去。大概是這本攝影集觸碰到生活某個真實的,卻沒有人願意談論的面向吧。如果一切都只是過程,是不是代表,沒有誰是不能替代呢?有時候執著於某個人、某個名字,不如像深瀨一樣,喝一大杯廉價威士忌,乘上持續移動的火車前往雪國,接受一切隨之而來的經驗。

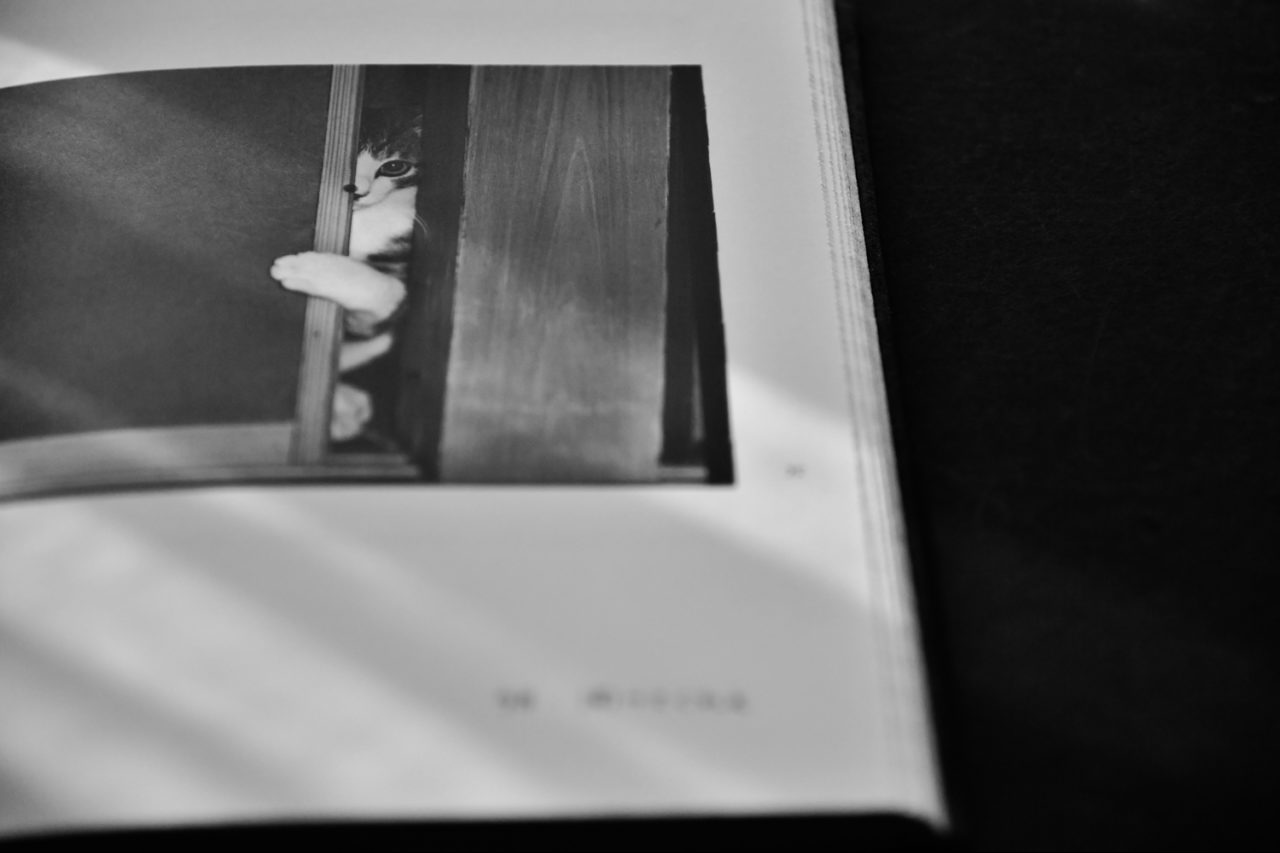

深瀨昌久曾經以相同的情感去拍攝他的妻子。她卻非常反感,認為他只看到鏡頭中的自己:「每一張有我的照片,也不過是他的自我投射而已。」深瀨為此痛苦著。洋子離開後,他想:「持續以拍攝深愛的人這樣的名目拍下去,不論是拍照的我還是曾經愛過的她,都無法得到幸福。攝影真的快樂嗎?」這個問題他無法回答,緊接出現的サスケ二代目,大概是深瀨的一個救贖吧。在每一張サスケ二代目的寫真中,我都看見對平靜生活的渴望,以及背後潛藏的痛苦。

過了三天,颱風離開了,天氣晴朗,就像夢醒一樣陽光明媚。離開大阪前,我打算和咖啡店裡的大叔隨便說幾句。但我沒有。像他這樣的男人,我想像不出他們的聲音。那個下午,吃過咖啡店裡不怎樣的蛋包飯後,我搭上前往四國的新幹線,在窗旁沉沉睡去。

In September 2018, Typhoon Jebi struck Kansai. As it drowned the international airport, I just so happened to be in Osaka, killing time at a coffee shop next to the hostel every day. In the dark coffee shop sat but one middle-aged man. He would place his coffee cup on the table, then retreat to his position to read the papers. I liked his reticence. Like sailors, he never spoke more than what was necessary.

As it neared dinner time, the wind was growing stronger, the sound of a trembling tin board came through the window and a black cat came in by the back door. The man deftly set up a towel, water and kibble for the cat. Such somber expressions must belie volatile emotions, I thought at once. The love of the mature man is truly a complicated and elusive thing.

I have been asked by a few friends before on what my favorite photography book is, to which I never answered straight away, but told the story of a man instead. When his wife left him, a reticent man decided to get a cat, which he namedサスケ(Sasuke). Ten days later, the cat ran away. The man desperately put up notices in search of it. After two weeks, a neighbor brought over a cat. At first glance, it looked a lot like Sasuke, but they were not the same cat. At that moment, the man thought, “There’s nothing I can do, I might as well take this cat for it.” And so, he adopted the cat, which he named サスケ二代目(Sasuke the Second). Wherever he went, he kept the cat by his side to take all kinds of photographs.

The name of this man is Masahisa Fukase.

In the year that followed, Fukase ventured the world with Sasuke the Second. During summertime, he brought the cat outdoors to enjoy the blazing sun and see elephants at the Ueno Zoo; In early autumn, they went to the Oiso seaside to see the ocean; Came wintertime, snow fun at the Yoyogi Park against the cold. At the bottom of the photographs, he scribbled scrawny letters to record all kinds of life events: “August: First tree climb”, “August: First leap across a little stream”, “January: New year’s snow”. Looking back on the year, Fukase said, “Most of the time I was crawling on the ground, taking photographs in the cat’s perspective. To an extent, I have become a cat too. This must be the happiest thing ever, taking photographs, having fun with a cat that likes me and experiencing the harmony of the four seasons.”

Every time I opened Fukase’s Karasu, I would read it in one go. However, each time I saw Sasuke the Second as captured under his lens, my heart grew heavy and I would no longer want to read on. Perhaps this photography book touches on a certain aspect of life that is true, but which no one wants to go into. If all is only a process, does it mean that no one is irreplaceable? Rather than hanging onto some person, some name, why not take it from Fukase – down a big pint of cheap whisky, step into an ever-moving train to the snow country and accept whatever experience that may come.

Fukase once photographed his wife with the same sentiment. His wife, however, resented it and thought he could only see herself through his lens, “Every photograph of me is but a projection of his own self.” This pained Fukase. When Yoko left, he thought, “To carry on photography work in the name of photographing loved ones brings no happiness, for both the photographer that is myself, and her, who I once loved. Does photography really bring happiness?” He could not answer this question. The arrival of Sasuke the Second soon after was perhaps Fukase’s redemption. In every portrait of Sasuke the Second, I saw the desire for the quiet life, and the pain underneath.

Three days later, the typhoon left. The sky was clear, sunny and bright as an awakening. Before leaving Osaka, I had meant to strike up a banter with the man at the coffee shop, but I did not. I could not imagine the voice of men like him. That afternoon, I ate a dull omurice at the shop, then boarded the Shinkansen to Shikoku and, sitting by the window, sank into a deep slumber.