五月時到日本的松本市參觀山本昌男的新書《Tori》的出版紀念攝影展……究竟能否說是攝影展呢?寫到這裡時仍有點懷疑。只有郵票大小的照片疊在小盒子裡;海灘的照片被鑲在小畫框內,照片裡是小石頭,而擱著照片的架子上,也堆放了山本先生從各處撿來的小石頭……山本昌男的作品,是攝影,也是裝置藝術。

山本先生自2008年起,已經不大作裝置藝術了,該次展覽的作品是應策展人的要求而選取的。不作裝置,也打算開始拍攝大張照片的山本先生,在新書《Tori》之中,仍然看到他對於作品展示形式的執著,以及透過展示空間來說故事的能耐。

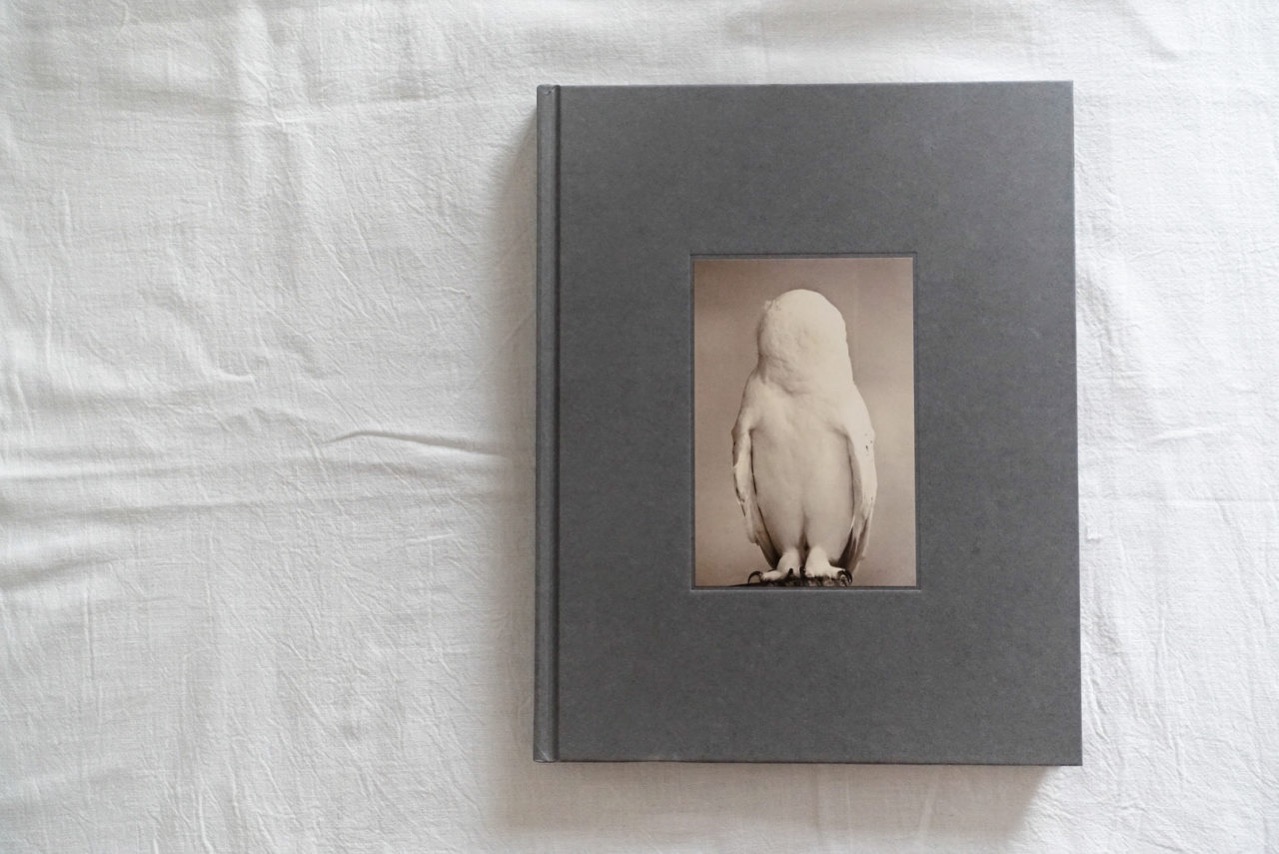

Tori是日語「鳥」的發音,山本先生對文字極為敏感。書中收錄的全都是跟鳥兒相關的照片,書籍又是在美國出版的,本來大可以用「Bird」作為名字。我猜,除了為強調日本的印象,或許是因為Tori同時也是「攝影」、「拿取」的發音。山本先生以往偏向拍攝小巧的圖片,能執在手裡的呎吋,與大部份攝影師不同,他不視攝影為通往別個世界的窗口,而視之為物件——一件記載了過去,同時也能冒充過去的物件。

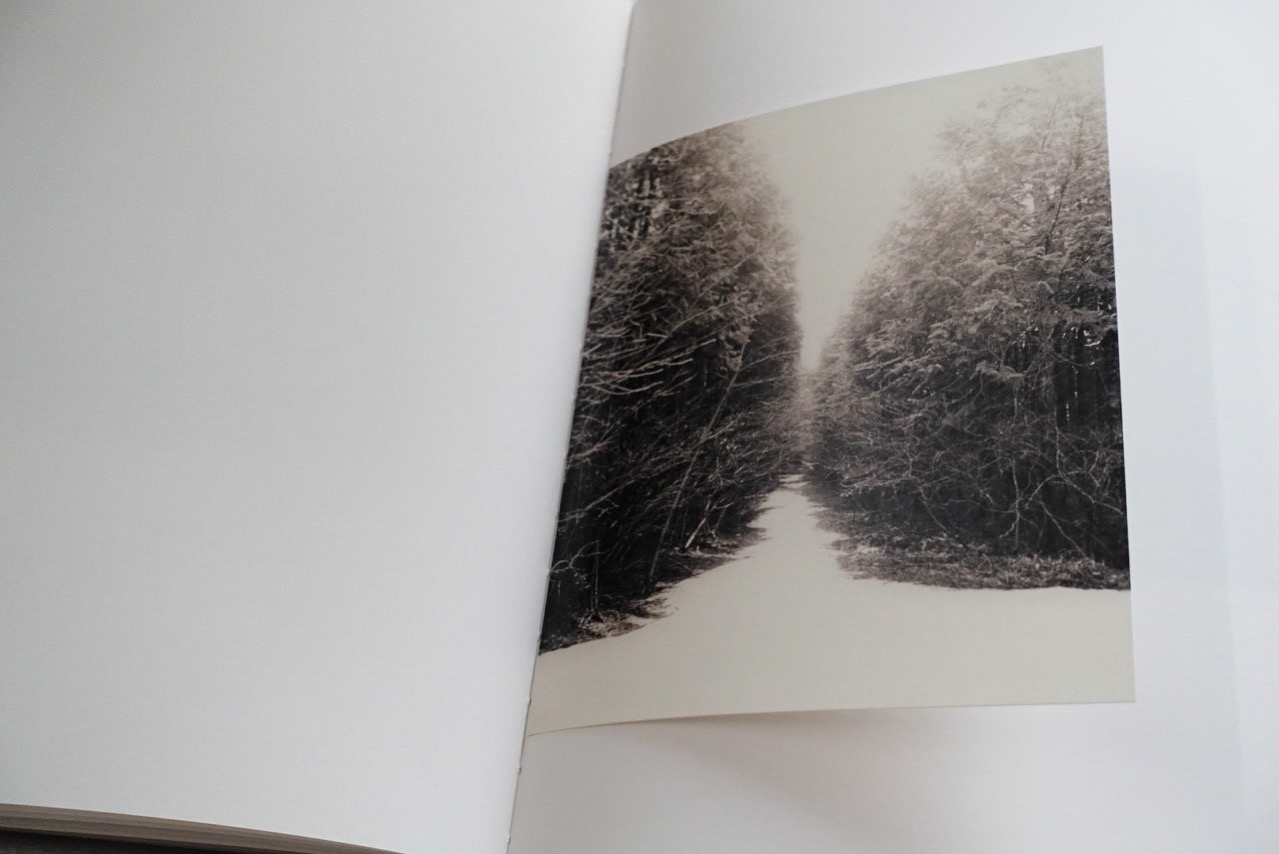

在山本先生的作品中,我們從來讀不出時間。他刻意照片泡在茶裡、耐心地揉過捏過,使它們彷彿自久遠的歷史中走來。他不以影像記事,而以影像在他攝影作品裡只是其中一項元素,助他描畫著他心中的故事。凝看他的照片,故事不在你眼前展開,卻邀請你潛進去,一同探研。

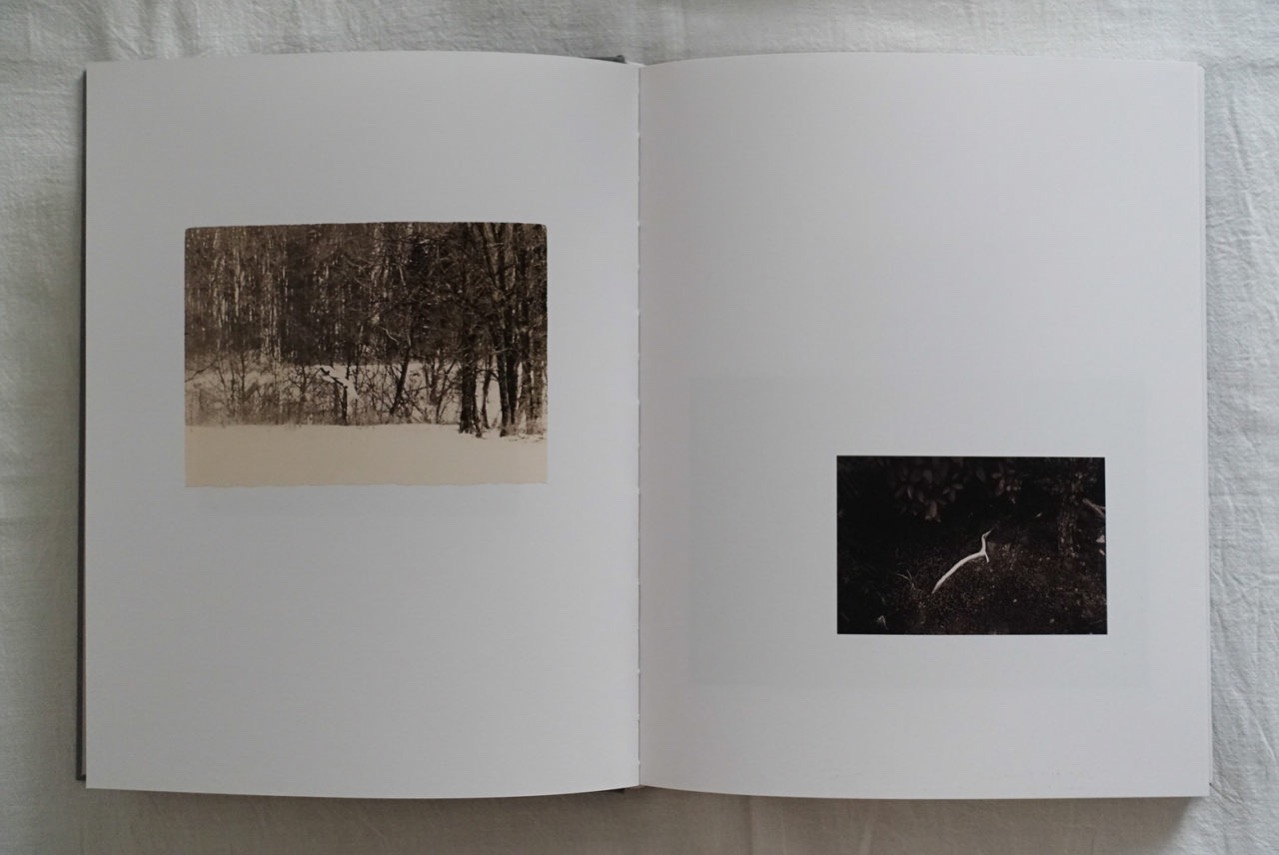

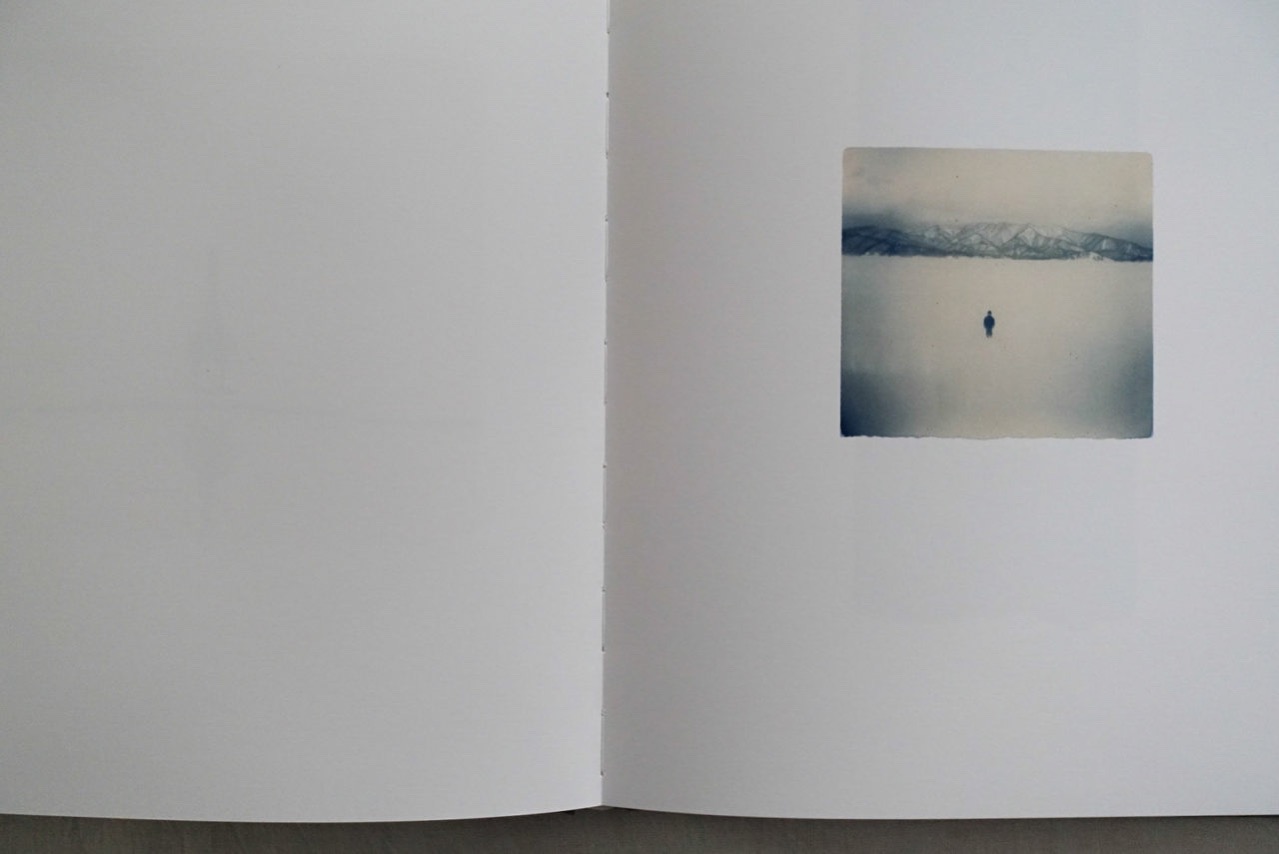

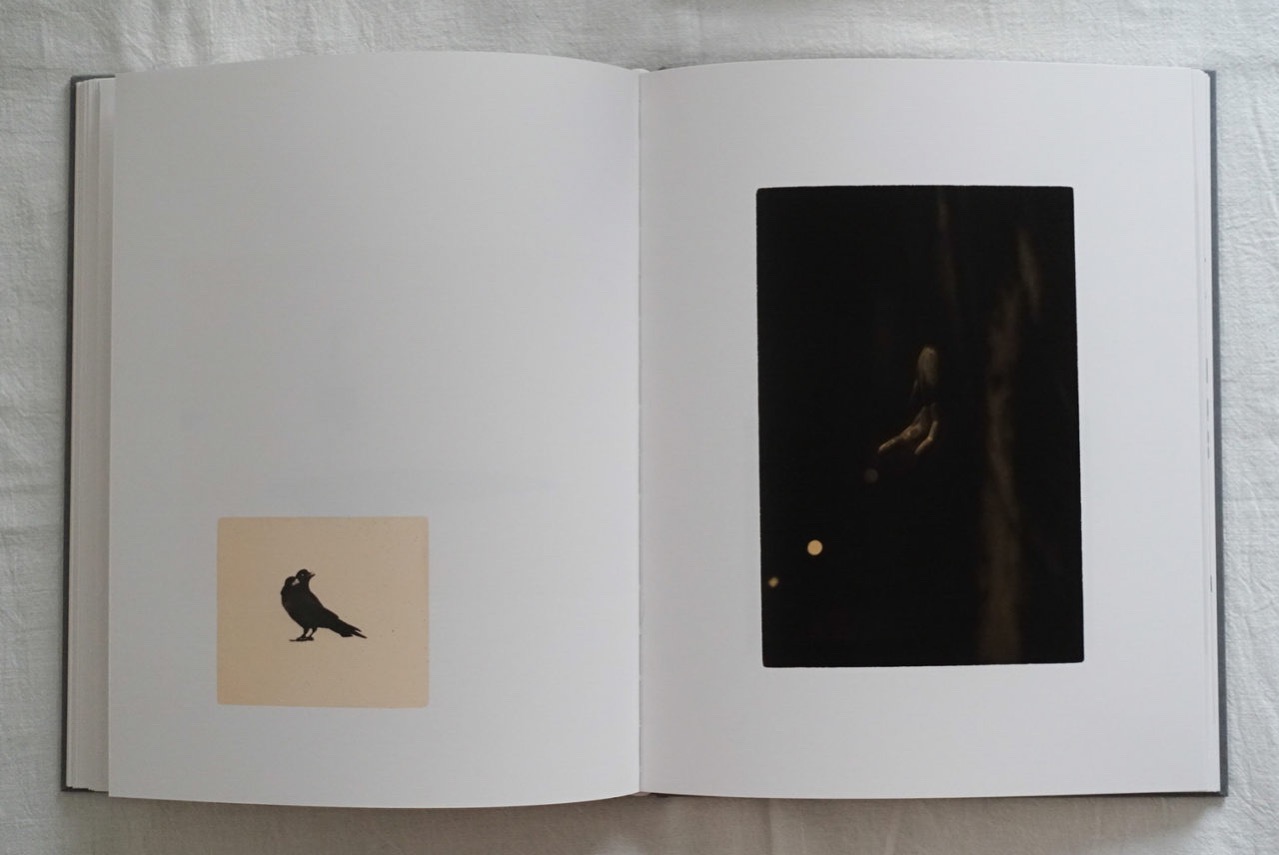

就正如山本先生的攝影展,《Tori》一書中有著大量的留白,好些時候,書頁偌大的空間,照片就一小幀地置在角落。左頁一張鳥兒,右頁的一幀似乎是佛像的手。鳥兒抬頭望,余白之中,妨似充滿了鳥兒對世界的疑問與憧景。山本先生的照片說故事,余白間也蘊含著無數情節,要我們逕自虛想。對我來說,這是山本先生作品最動人之處。

I was in Matsumoto in May to visit the photography exhibition that celebrated the launching of Tori, Masao Yamamoto’s new book. However, up to this moment, I am still in doubt if it can be considered a photography exhibition? Some photos were printed at the size of a stamp and stacked together in a small box, some photos of beaches are mounted in small frames, and pebbles collected by Yamamoto were placed in front of some photos of pebbles… Masao Yamamoto is not merely a photographer, but also an installation artist.

The works showcased in the recent exhibition were chosen based on the curator’s request. Yamamoto has seldom done any art installation since 2008; along with the fading presence of his art installation, Yamamoto began to work on photography of large formats. Regardless of the shift in his creative direction, Tori still vividly shows Yamamoto’s dedication to the presentation of his work, as well as his ability to utilize space as a medium of storytelling.

“Bird” in Japanese is pronounced as “tori”. All the photos featured in Tori are related to birds. Yamamoto could have used Bird as the book title since it was published in the United States. I guess, on one hand, Yamamoto would like to stress on the Japanese vibe; on the other hand, driven by his love for language, he wanted to retain the multiple meaning connected to the pronunciation “tori” — a pronunciation that can also mean “photography” and “to take”. Yamamoto used to focus on making small sized images that can be easily held in a hand. Unlike the majority of photographers, he does not see photography as a window to another world; it is to him an object that records the past, or can even disguise as the past.

The concept of time is never quite traceable in the work of Yamamoto. By deliberately soaking the printed photos in tea and wringing them carefully, the images transcend time and can be easily mistaken as historical photo prints. Yamamoto does not see image as a mean for documentation, but merely as one of the elements that help to narrate the stories that he yearns to tell — these are the stories that do not unfold themselves for the audience, but invite audience to delve into the photos to actively explore with their own imagination.

The book Tori adapted the style of Yamamoto’s exhibition to deliberately leave a good amount of empty space. Quite often a photo only occupies a tiny space at the corner of an almost blank page. Flipping open the book, image of a bird is on the page to the left, to the right is supposedly the hand of a Buddha statue. The bird is looking up to a piece of emptiness, can this be the uncertainties and aspiration the bird has towards the world it exists? The empty space — the very part that deeply moves me — is essential to Yamamoto’s narrative, as it contains numerous stories waiting to be unfolded by readers’ imagination.