「親愛的兒子,我沒有什麼可以為你慶祝婚事,最少也得為你造張被子,但是現在我只能夠把我為你父親所造的兩件和服傳送給你,一件已穿舊了,另一件是新的,你就以它們來紀念我和你的父親吧!」媽媽雖然走了,看著和服上以兩塊布縫合起來的無數刺子繡針步,便感受到她為丈夫所付出的全副精神和心機。

回想起兒時祖母看見我在把玩較剪和布片,就會説:「你要知道你正在剪自己的肉!每一塊布裡頭都住着一個生命和交織着人類無數的意志和願望。」布料和衣物對江戶時代的女性是猶如生命般重要。

“My dear son, I’ve got nothing to give you for your wedding. I wish I could make you a futon, at least. But all I can offer are two Sashiko kimonos (quilted farmers’ jacket) I’ve loomed for your father. One is worn out, the other is good as new. Take these to remember us.” My mother is gone, but woven into the quilted jackets, stitch by stitch, is the legacy of her love and devotion.

I used to toy with scissors and fabric when I was little. My grandmother would tell me off, “To slash cloth, you are slashing your own flesh.” She said there was a life force dwelling in every piece of cloth. In the Showa era, women depended their livelihood on fabric.

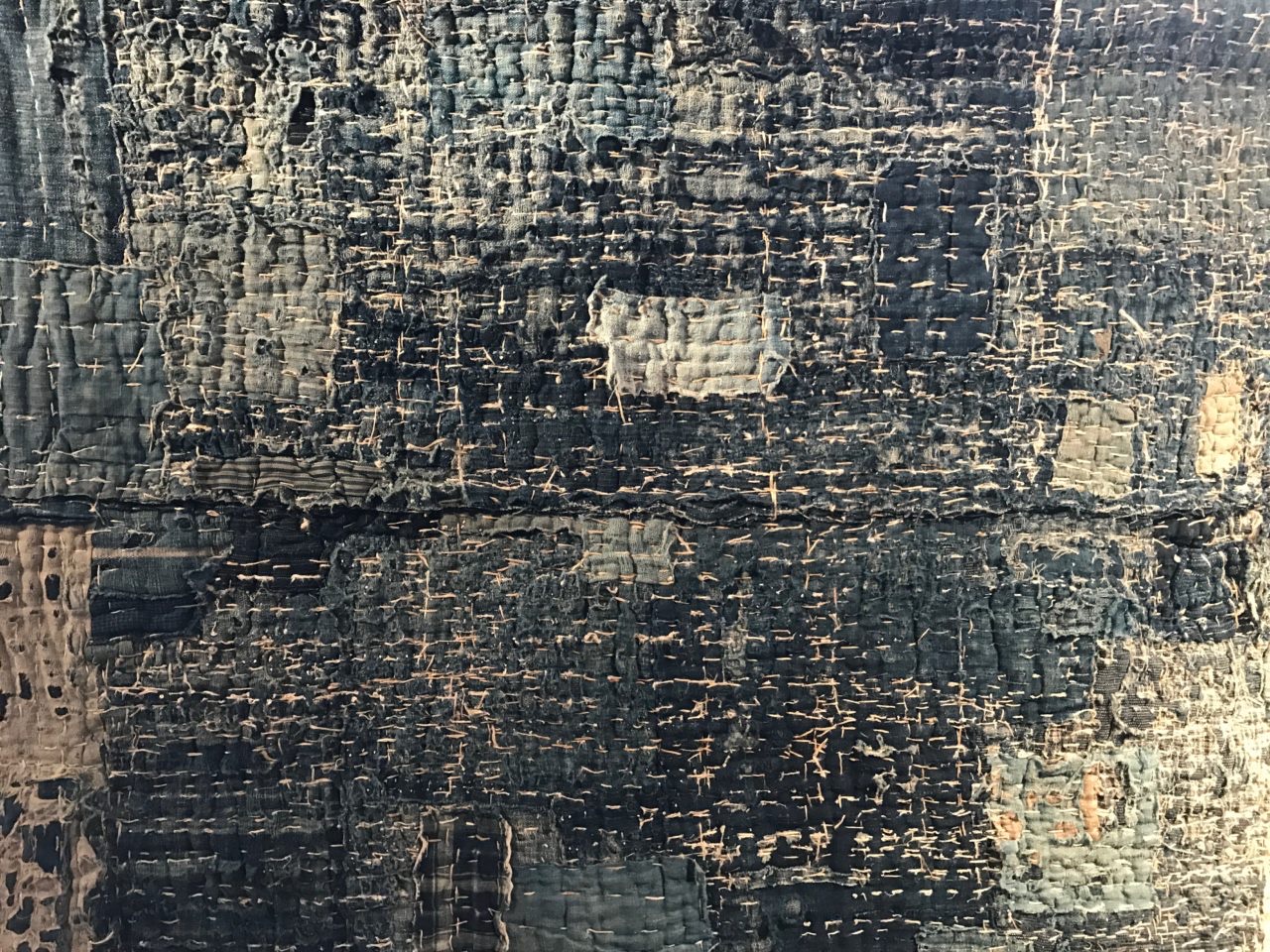

尤其在昭和時代前,日本的東北 —— 雪之國度,本洲最北邊的青森縣,象徵日本最貧窮的地帶,農夫和漁民,因為嚴峻的天氣,土地貧瘠,連棉花也長不出來,只能以緊絀的麻布造衣,人們不分晝夜和場合,只穿同一套衣服,並不斷重疊布碎來修補和加厚,以防寒和補強之用。BORO(襤褸)直譯是爛布的意思,這種簡單多變、迷倒當代布藝設計的縫補針法,卻是這片荒蕪之地的生存之本——用之美。

Before Showa, Aomori Prefecture in Japan’s Tohoku region – colloquially referred to as “the snowed kingdom”, had been notorious for its poverty. It was too cold to grow cotton, so the local farmers and fishermen grew hemp instead and created a textile aesthetic known as boro: derived from the Japanese boroboro, which means “something tattered or repaired”, boro refers to the practice of reworking and repairing textiles through piecing, patching and stitching. Born out of necessity, boro has since evolved into works of art that champion the beauty of practicality, and a cultural record of homespun cloths, dyes and techniques.

刺子繡,於16世紀初、約五百年前誕生,最初是以藍染棉布白線以約一粒米距離的小刺行針刺繍而成,相傳喻意藍天白雪的景象。有興趣可參考我的教學慢下來試試。

Sashiko originated in early 16th-century Japan. Its name means “little stabs” – a reference to the plain running stitch that makes up sashiko’s geometric, all-over patterns sewn with off-white stitches on dark indigo fabric, evoking whitecaps on the ocean, or dark blue mountains topped with snow. You can try it out with my tutorial.

在地上鋪上稻草和Bodo,爸媽就包裹在像加大碼夾棉和服的Donja中間,而赤裸的孩子們就鑽進他們的兩旁依靠,互相緊緊地抱著的體溫,度過睡夢中的晚上。

Donja是一件晚間的大被子,不是那種輕柔的間棉睡衣,而是以又厚又粗糙的布及很多層麻布托底縫合而成的,為了抵禦北部嚴峻致命的寒冬,越厚越好的Donja是必須的。

A family makes their bed by spreading straw on the floor and laying a bodo rug over it. Cocooned in a donja, the parents would sleep in the middle, their children huddling up naked next to them.

Donja is a huge night blanket. Unlike regular, lightweight blankets made of cotton, donjas are heavy, layered and made of quilted hemp cloths. A heavy-duty donja is a necessity for the harsh winters in the northern prefectures.

Bodo或Bodoko常用作床墊,當時的婦女在生產時會拉著從天花板懸垂的繩子,蹲在Bodo上產子,這些布墊是從祖先們穿過的衣物和布碎一層層縫叠起來,集合了祖先們的祝福和叮嚀。

「每個人都能輕易從過去10個世代追溯到1000個祖先的生命,沒有他們的扶持,我們就沒有獨自站立的今天。」

Bodo or bodoko is a bed sheet made using the technique of patching hemp and cotton cloths together. In the old days, women would crouch on a bodo as they gave birth, holding onto a string from the ceiling for support. Bodo is a family heirloom made of clothing and fabrics worn by one’s ancestors, sacrosanct for the well wishes and reminders it carries.

“We can easily trace our family tree back to a thousand ancestors through the past ten generations, without whose support we would never be here today, as self-sufficient individuals.”

在一個僻遠的山區住着一位老婆婆,平靜地訴說著她的故事,她堅持獨自留守這被遺棄的房子和附近的墓碑,因為她深信這是一個和先人們連結在一起的神聖之所。

「我不感到孤單,我正在等待和他們再次團聚,在這之前,我正活在他們留下來的回憶中。現在的我已沒有貪念,所以也沒有紛爭。貪婪只會傷害別人,甚至傷害自己;只有當我們能夠擺脫內心的貪婪,我們才能回歸自然和土地上。你喜歡舊物嗎?在這裡拿一件東西留作對這老太婆的紀念吧!」

這裡的每件東西都彷彿有著心跳、溫度和用過它的人的故事。

An old woman living in the mountains tells me her story. She lives alone in the depopulated area, gravestones as her neighbours, in honour of the land’s scared connection with her ancestors.

“I don’t feel lonely; I’m waiting to reunite with my late folks. Until then, I’m just living in the memories they’ve left behind. I have no greed, and therefore no quarrels with anyone. Greed can only hurt others and eventually yourself. Only after we have ridden ourselves of greed are we able to reunite with nature – with earth. Do you like antiques? Fancy some memorabilia from an old woman?”

Each object in the house pulsates with the warmth of its owner – and her stories.

「為了遺物邊哭邊爭」,在青森縣有這個古老的説法。意思是在葬禮上人們在哭泣的同時也不忙爭奪亡者的衣物,因為當時物資都是配給制的,不是有錢就可以買到,可見衣物對這雪嶺上的人來說有多重要。

人們曾經對於剩餘物資的珍重而衍生了令我印象深刻的日文詞「Mottainai」,是「太可惜了」的意思,不只用來形容布料,或食物或物件,甚至是當有親友離世時,用來表達這麼好的人離開了實在太可惜了!

There is a popular saying in Aomori, “To mourn the deceased and fight over their relics at the same time.” Herein evidenced the scarcity of rations then and the importance of clothing to mountain people.

The Japanese term mottainai, which translates as “What a waste!”, emanated from this scarcity. It conveys a sense of regret over waste of precious food, clothing or objects, but also – the loss of a loved one.

在工業革命之前,衣服都是充滿愛的,一針一線,每一塊布都是由媽媽或是媽媽的媽媽編織、縫紉而成,當中包含了家族的故事、歷史和傳承;甚或是關於愛情的故事,有妻子造給丈夫的,也有男生為未來妻子遮風擋雨而造的稻草雨衣 ⋯ 那麼現在由別人的媽媽和妻兒日以繼夜所造的廉價衣裳,當中又包含著什麼意思呢?

Before industrialisation, clothing used to be a work of love, woven with care by mothers as vehicles of family tales, history and legacy; or by wives and husbands as a mino (a traditional Japanese raincoat made out of straw) for their loved ones. What meaning, then, does our modern, mass-produced clothing – handmade by other people’s mothers and wives, carry?

場館內掛了34幅都築嚮一先生的攝影作品,築嚮一先生亦是BORO Rags and Tatters from Far North of Japan的作者,在我的SLOW STiTCH NOMAD網頁內也有介紹。

34 of kyoichi tsuzuki‘s photography were hung in the museum, he is also the author of “ BORO Rags and Tatters from Far North of Japan” which is also mentioned in my SLOW STiTCH NOMAD webpage.

「Amuse Museum 開館十週年特別展覽」

感謝民俗民具研究家和收藏家田中忠三郎先生,走遍青森縣的農村和漁村去搜羅以青森縣為中心、所收藏的江戶時代至昭和初期的BORO衣物和生活用品,讓我們有機會感知這些動人的故事,提醒我們得來不易的民間智慧。

有機會到東京一定要親身再去感受一下!

布文化と浮世絵の美術館

111-0032 東京都,台東區,淺草2-34-3

“Amuse Museum 10th Anniversary Special Exhibition”

This exhibition features boro textiles and archival pieces from the collection of Aomori native and ethnologist, Chuzaburo Tanaka (1933-2013), who dedicated his life to researching and documenting the culture and wisdom of his home.

A trip to Tokyo is not complete without a visit to the exhibition.

The Textile Culture and Ukiyo-e Art Museum – Amuse Museum

2-34-3 Asakusa, Taito Ku, Tokyo, Japan 111-0032