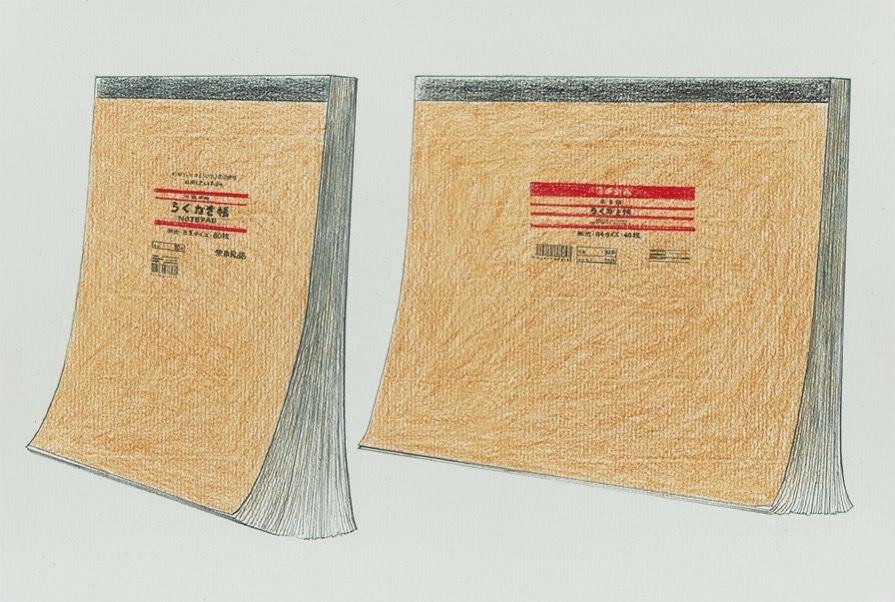

村上春樹在《身為職業小說家》一書中曾提及,他覺得要隨身攜帶筆記本是很麻煩的事情,所以寧願把所有東西保管在腦子裡,因為他相信真正重要的事在放進腦袋以後,是不會那麼容易被遺忘掉。這方面我跟村上春樹某程度上是相近的人,沒耐性有系統地用紙筆記下各種點子想法,腦袋卻好像是懂得自設文件櫃似的,要想起什麼的時候,那個相關的抽屜便會自動打開來。可是,我卻又一直暗暗痛恨自己沒法成為能夠好好使用筆記本的那類人,每次遇到漂亮的本子,心癢癢的買了回家去,在寫過十多廿頁以後,便又把筆記本擱在被遺忘的角落裡。最近沉迷的筆記本款式,就是無印良品以再造紙製作的這一系列,那粗糙的紙質無疑吸引,但真正令我心儀的,是撕下這類粗糙紙張的手感。沒錯,我就是有一種怪癖,一堆從沒填滿的筆記本子在擁有了一段時日以後,我是會喜歡把那些寫了零碎字句的紙頁從各個筆記本中逐一撕下,然後再捆好或是摺疊在一起,並且安放在一個紙盒內好好收藏。如此這般才好像是終於能把散落的思緒給好好整頓了一樣,心裡才確切地感到踏實起來。

沒有持續使用筆記本進行書寫紀錄,並同樣擁有類似的紙張收集怪癖,原來亦另有其人。他就是卡夫卡和班雅明也曾仰慕的瑞士作家羅伯特‧瓦爾澤(Robert Walser)。生於1878年的瓦爾澤,年輕時因無法單靠寫作為生,便也同時幹過不同職業,當中包括銀行及保險公司職員、科學家助手和家庭佣人等。1929年以後一直長居精神病院,閒時喜愛獨自散步,廣為後世相傳的住院名言是:「我待此處不為寫作,是為瘋掉。」死後留下一個舊皮鞋盒,內裡裝滿526張廢紙,有從月曆撕下的紙頁、出版社寄來的信封殘骸、自雜誌剪下的紙張、編輯的回覆卡片、郵寄包裝紙、陌生人名片、過期車票等,上面密密麻麻填滿只有一至兩毫米大小的鉛筆小字,一度讓人誤以為是無法解讀的密碼,卻原來是其生前未曾發表的散文及詩作手稿。頭一趟在《Microscripts》一書看到瓦爾澤的手稿圖片時,立即想到了艾蜜莉‧狄金生(Emily Dickinson)也極愛利用信封殘骸寫詩。一位長年把自己關在瘋人院內,另一位則終其一生隱居家裡,二人除了刻意與世隔絕,另一共通點就是熱愛暗地裡讓零碎的紙片開枝散葉。看著這些在廢棄紙張上開過的花結了的果,似曾相識的感覺再度浮現。也許,他倆就只是想要借助看似無足輕重的瑣碎書寫姿態,述說曾幾在遙遠的時空裡浮現一瞬華麗的告白,並且順道跟此時此地的我,似有若無地,輕輕揮手吧。

In As a Professional Novelist, Haruki Murakami has mentioned that he thinks carrying a notebook is very troublesome, so he would rather store everything in his mind, as he believes the truly important things would not be so easily forgotten once they are stored this way. In this respect, I am kind of similar to Murakami in that I also don’t have the patience to jot down various ideas on papers, but my mind seems to have already set up a file cabinet system, and when I need to remember something, it will automatically pop out from a specific drawer. However, I have always secretly hated myself for not being able to become the kind of person who can make use of notebooks for recording things. Every time when I see a beautiful notebook, I could never resist not buying it home, but after I’ve filled up some of its pages, I would give up and leave it in a neglected corner. Recently, I have fallen in love with this Muji notepad series made with recycled papers. The rough texture is undoubtedly attractive, but what really appeals to me is the feeling of tearing off such kind of paper. Indeed, I have this quirk – upon accumulating a bunch of half-filled notebooks, I would always tear off the written pages from every one of them, carefully bundle or fold them together and find a paper box to store them inside. It seems that once I do this, my scattered thoughts are finally gathered, and my heart will find reassurance again.

It turns out someone else also didn’t like using notebooks and had a similar quirk for collecting pieces of written papers. His name is Robert Walser, the Swiss writer once admired by Franz Kafka and Walter Benjamin. Born in 1878, the young Walser was not able to earn his living solely by writing, and he had to take different jobs as well, including doing clerical work at a bank and insurance company, worked as assistant for an inventor and also served as a butler. From 1929 and onwards, Walser had been living in various mental hospitals. He had always enjoyed taking walks by himself and his famous saying during his hospitalisation was, “I’m not here to write, but to be mad.” He left behind a shoe box after his death, which contained 526 scraps of papers, including sheets torn from calendars, envelopes sent by publishers, pages cut out from magazines, paper cards with replies from editors, wrapping papers from postal packages, business cards from strangers, expired train tickets, etc. They were all filled with pencil writings as tiny as one to two millimetres. They were once mistaken as indecipherable secret codes, but later recognised as his unpublished manuscripts of proses and poems. The first time when I saw the photos of these paper scraps in Microscripts, I immediately thought of the envelope poems written by Emily Dickinson. One had kept himself in madhouse for many years; another had lived like a hermit all her life. Apart from deliberately isolating themselves from the rest of the world, they also had another thing in common: the passion of developing an archive of written paper scraps. As I look at them bearing fruits and blooming flowers, a kind of Déjà vu feeling emerges. Perhaps the two of them would like to use these seemingly insignificant writings to gather something gorgeous from a distant time and space; and while doing this, they also gently wave at me, as if nothing ever happened.