走在路上,安西淳會特別留意沿路的花草,他會拾起喜歡的一小棵植物的枝節,安放到他親手做的乾漆小花瓶中,小巧精緻的花瓶裝飾了平淡而溫暖的家。

漆藝師安西淳曾於被自然美景圍繞的輪島,跟隨「日本現代漆器十二人」之一的赤木明登研習漆藝,七年後自立門戶,繼續承傳和發揚傳統漆藝的美好。「畢業後在一家飲品公司工作,後來公司轉用機器生產來增加產量和效率,便開始發現自己不喜歡冰冷的工廠式生產,並萌生學習傳統手工藝的念頭,感受親手製作和使用有溫度的工藝品。後來在京都傳統工藝學院學習期間,四處看展覽而認識了漆藝,立刻被深深吸引著,便決心拜師學藝。」

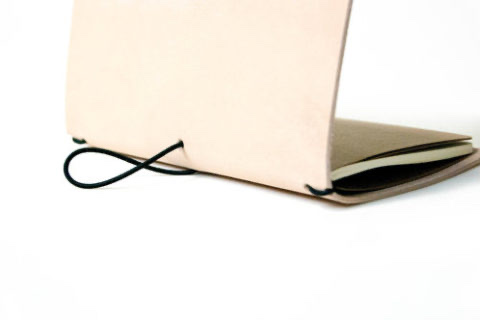

漆器起源於江戶時代,被視為奢侈的裝飾品,在特別的場合才會使用。安西淳師承了赤木明登,把漆藝放到日常生活之中。「老師說我們要精於一種技藝,而我想做一些實用性高、能於日常使用的工藝品。乾漆非常輕巧,可塑性高,表面看來可以像青銅、陶瓷和黏土,但只要一拿起就會驚訝於它如一張紙般輕巧,而且堅固耐用,適合日常生活的需要。更重要的是,我要把學習到的技術加上個人的轉化,而不是直接抄襲。」安西淳常常被問到師父的作品多以木胎漆為主,為何他卻採用了乾漆技術,「乾漆可以模仿不同的物料,並予人似重若輕的感覺。我喜歡收集植物的枝節,把它們放在細小的乾漆花瓶中,有一種剛剛好的圓滿感。」看似輕巧細小的漆器卻是滿載工匠厚重的心意。

乾漆在中國可稱為「夾紵」,是脫胎漆藝的技法之一,始於戰國時代的楚國,早年用於佛像製作,後傳至日本。乾漆技法是先利用土或木製模具(內胎),然後以麻布的張力按在模具,將麻布跟漆層交互重疊,待乾固後把內胎除去,最後剩下漆和布的結合體,使器物輕盈而堅韌。安西淳的作品都是使用天然漆製作,天然漆是漆樹受傷時湧出的汁液,用以覆蓋樹枝上的傷口,漆乾後如疤痕般變得堅硬乾結。因此,塗上天然漆的器具表面也像皮膚般懂得呼吸,盛載熱茶後能平衡溫度,不會熨手;用久了,顏色也會變得溫潤,使漆器變得有歲月的質感。

製作的過程中,工匠無法看到器皿的內裡,只能相信自己的手和依靠直覺去造,「我運用傳統的技藝把乾漆以全新的外形呈現,希望年輕人也能如我般喜歡有溫度的傳統漆藝品。」安西淳的作品擁有簡約的造型和線條,不刻意嘩眾取寵,安靜地於角落裡散發沉靜優雅的氣氛。

Wandering on the streets, Jun Anzai has a habit of observing the flowers and weeds on the side of the road. He would pick up a branch of a small plant and place it in his handmade lacquer vase, which is a humble and delicate decoration to his minimalistic warm home.

Before becoming a master of lacquerware, Anzai was once a student of Akito Akagi, one of the twelve most important lacquerware artists in Japan. After learning from Akagi for seven years, Anzai set up his own workshop to promote the beauty of lacquerware. “I got a job at a drinks factory after graduation. The factory soon switched to industrial production for a better efficiency and productivity. Then I realized the coldness of machine industry was not what I looked for and began to have a desire to learn some traditional crafts. I wanted to use my own hands to create and use crafts that carry a personality. Later on, I was enrolled in Kyoto College of Traditional Arts. Walking around the campus to check out the exhibitions, I got to learn about the art of lacquer. I was totally intrigued and determined to learn the skill.”

The history of lacquerware can be traced back to the Edo period as a luxury decoration that was used only on special occasions. Learning his skills from Akito Akagi, Jun Anzai tries to bring lacquerware into everyday life. “My teacher said we need to master a certain skill. To me, all I want is to make practical craft items for daily use. Lacquer is a very light material that has great potential. Its surface sometimes resembles bronze, ceramic or clay, but once you pick it up, you would be surprised by how light it is. Lacquerware is also very durable, which makes it a perfect household utility item. The most important thing is to give the skill I have learned a personal touch instead of blindly replicating.” Sometimes people would ask Anzai, why does he use the Kanshitsu (dry lacquer) skills but not following his teacher Akagi’s wood-body lacquer skill. He said, “Kanshitsu can imitate various types of material. Its existence lingers between heaviness and lightness. I enjoy collecting tree branches and put them in a tiny Kanshitsu vase. This gives me a sense of wholeness.”

Kanshitsu is a technique originated from the State of Chu during the Warring States period in China. In its early phase, dry lacquer was used in making Buddha statue. It was later introduced to Japan. The technique requires a model made of clay or wood. The next step is to tightly mount multiple layers of hemp cloth and lacquer onto the model that is to be removed once the cloth dries up. Since the end product is made of merely hemp cloth and lacquer, it is sturdy yet light. Anzai makes his lacquerware with natural lac resin, the fluid that a plant secretes as a response to injury. It would get rock solid once dried. Lacquerware covered with lac resin can breathe well and is adaptive to temperature change, therefore, the surface can maintain its coolness when serving hot tea. Its color also gets milder after being used for a long time, so every of the lacquerware can carry their own texture of history.

In the production process, it is impossible for the craftsman to look at the inside of the item; they can only believe in their experience and instinct. “I am trying to give Kanshitsu a fresh face using the traditional technique. I hope the younger generation can embrace the warm tradition of lacquerware as much as I do.” Anzai’s lacquerwares have a simple and minimalistic design. Instead of being bold and special, they would quietly elude their calm and elegant charm.

The Gallery by SOIL G/F, 52 Po Hing Fong, Sheung Wan, Hong Kong