我是一個喜歡留在家的人,除了去書店、戲院和偶然去喜歡的愛爾蘭酒吧之外,基本上不太出門。但在疫症那幾年,出於某種自己也不清楚的原因,我幾乎每日都會漫無目的去些什麼地方。無人的街道有一種從現實溢出的莫名吸引力,幾乎就像基里訶的油畫似的。

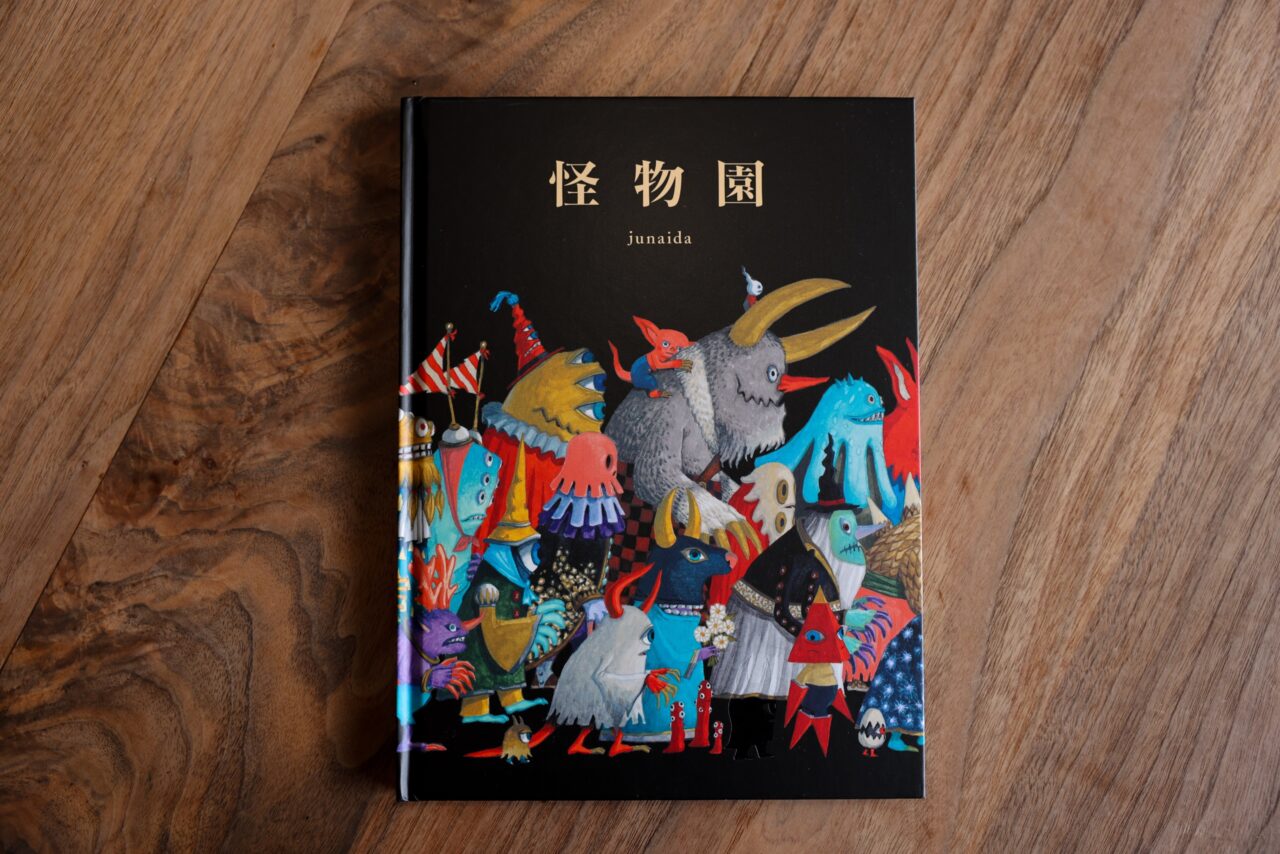

讀到junaida的繪本,完全是出於偶然。疫情過後,在東京吉祥寺一家不起眼的獨立書店的角落,放著這位出生於京都的藝術家的作品。漆黑的封面上,色彩鮮豔、身體莫名奇妙地長了古怪眼睛的怪物們向前前進,簡潔地寫著怪‧物‧園三個字,令人感受到安靜和狂歡的衝突氛圍。

我是一個喜歡留在家的人,除了去書店、戲院和偶然去喜歡的愛爾蘭酒吧之外,基本上不太出門。但在疫症那幾年,出於某種自己也不清楚的原因,我幾乎每日都會漫無目的去些什麼地方。無人的街道有一種從現實溢出的莫名吸引力,幾乎就像基里訶的油畫似的。

讀到junaida的繪本,完全是出於偶然。疫情過後,在東京吉祥寺一家不起眼的獨立書店的角落,放著這位出生於京都的藝術家的作品。漆黑的封面上,色彩鮮豔、身體莫名奇妙地長了古怪眼睛的怪物們向前前進,簡潔地寫著怪‧物‧園三個字,令人感受到安靜和狂歡的衝突氛圍。

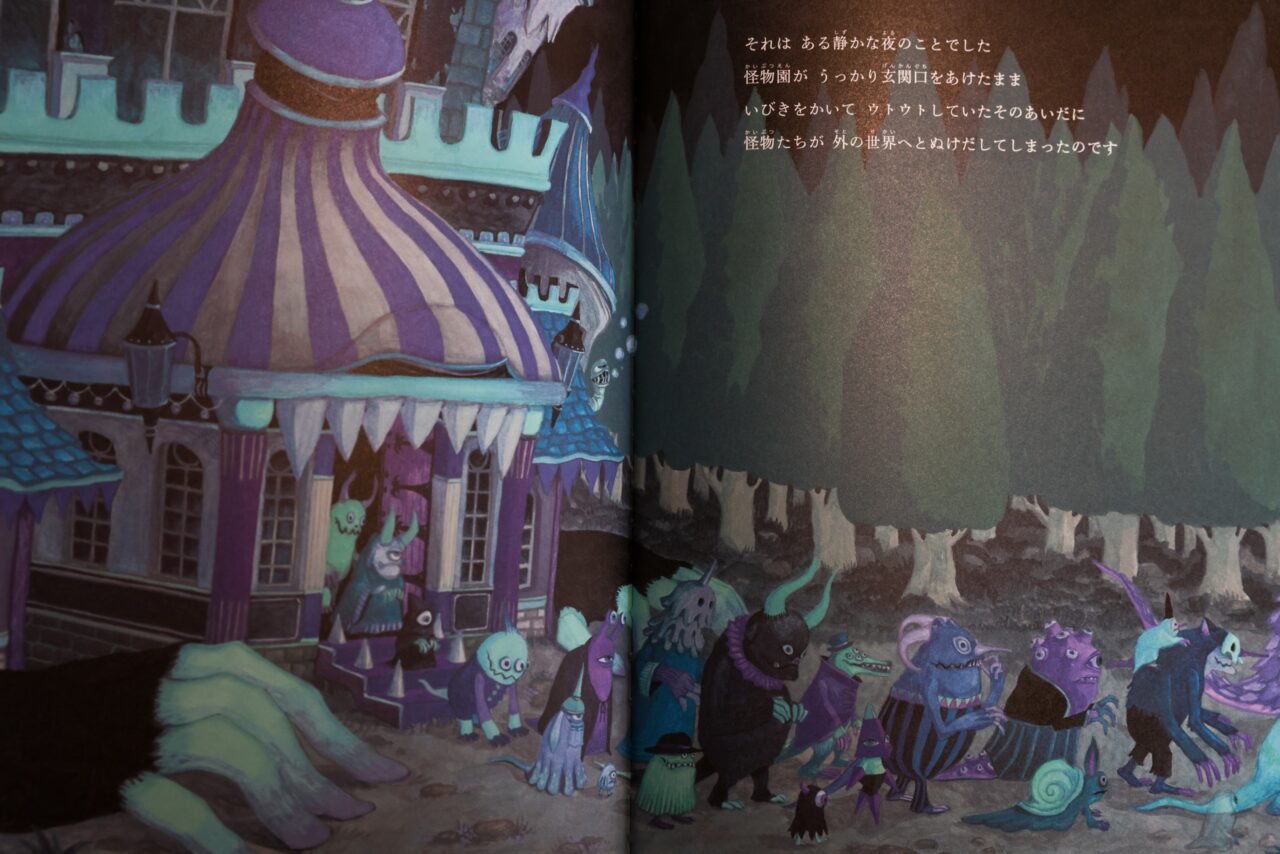

故事講述一個從遠古就開始在地球上四處漫遊的怪物園,某個晚上因為打瞌睡而沒關好門,讓住在裡面的怪物一隻接一隻走了出來。怪物們來到一個小鎮,令本身的居民害怕得四處躲避、不敢出門。沒有人知道怪物的目的地,但每次望出窗外,都看見怪物們慶祝祭典的遊行似的,列隊在黑夜的大街上緩慢前進。

雖然說是怪物,但仔細看的話其實一點也不恐怖,甚至說是可愛也不過份。牠們令人想起某種進化錯誤的生物,然後形成一個怪物的社會。長著蛙撲,穿著斗篷的鳥、長著八顆眼球的八爪魚、衰老得幾乎只剩下骨頭的象、流著紅色的眼淚,看起來非常悲傷的毒傘菇等等,或者,牠們多年以前曾經只是隨處可見的生物,出於某種原因,可能快要死去,或是被群體排斥之後,偶然進入怪物園生活。之後,經歷漫長時間的演化,才長成現在這個模樣。

故事另一條主線,就是因為夜行怪物而無法出門的三位小孩。整天無所事事,他們只好用身邊的事物解悶。他們將紙箱想像成冒險的巴士,將浴缸想像成飛船和潛艇。在這個故事中,大人似乎不存在。每日,孩子們都用身邊的事物編織成有趣的想像,與家裡養的賓士貓一起感受著想像世界中的太陽微風。

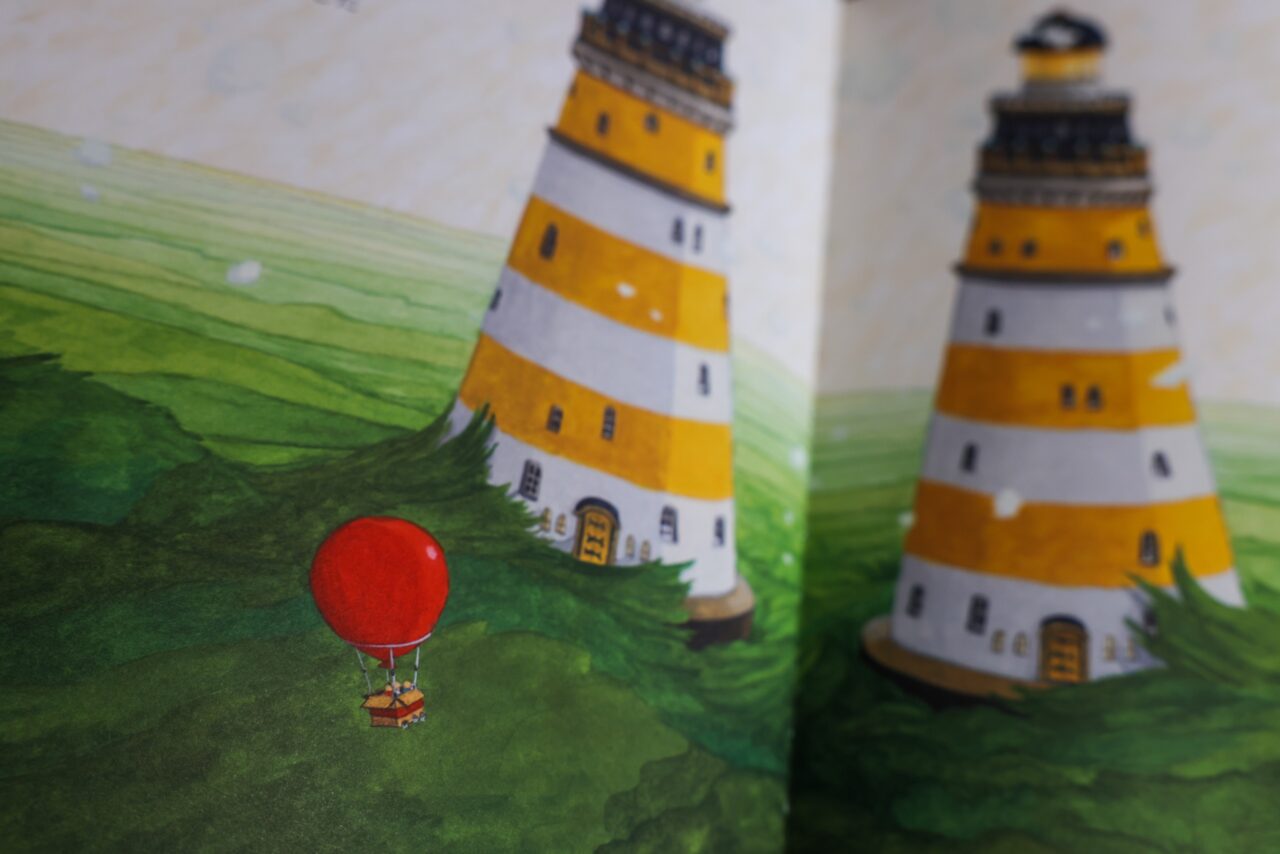

孩子們在想像的海底裡遇到一群走失的怪物。為了送牠們回家,孩子將潛艇改造成適合怪物生活的形狀,然後出發,前往「怪物園」。junaida並沒有畫出這個過程。我們只是讀到正在睡覺的孩子,以及在他們身旁的,讓人想起怪物園的馬戲團玩具。

清晨,醒來後的孩子們站在無人的街道上,怪物們經已離去。最後一幀畫,是怪物園再一次在森林中,朝著遠處的群山緩緩前進。這是孩子將怪物們送回家後,送別怪物園的風景嗎?我不禁想像,他們將怪物送回家後,獲邀走進怪物園裡,在舖了白檯布的圓木桌上享用了一頓奇怪但又說不出美味的下午茶。

當然,我知道這故事隱含了疫情的隱喻,但這樣去讀的話實在無趣。我還是傾向相信這一切都曾經發生。

闔上繪本後,我呷了一口guinness。這時,我在上野一家稱為The World End的愛爾蘭酒吧。疫情過後,城市的街道上再次擠滿了人,匆忙前往各自要去的目的地。我試想像著,在外面,某個看不見的遙遠地方,怪物園正邁著笨拙的步伐,一邊發出叮鈴噹啷的金屬碰撞聲音,一邊緩慢地向前走著。

I enjoy staying home. Apart from visiting bookstores, theatres, and occasionally my favourite Irish pub, I rarely go out. During the pandemic though, for reasons I couldn’t quite understand, I found myself wandering aimlessly almost every day. The deserted streets had a surreal allure, reminiscent of Chirico’s paintings.

I stumbled upon junaida’s picture book purely by chance. After the pandemic, I found this Kyoto-born artist’s work in a small, unassuming independent bookstore in Kichijoji, Tokyo. The black cover featured vividly coloured monsters with bizarre eyes, marching forward, with a neat title written across: “Monster Park”. It evoked a sense of both tranquility and celebration.

The story is about a moveable monster park that has roamed the Earth since ancient times. One night, the park’s gate was left open by accident, and the monsters began to wander into a small town, scaring the residents into hiding. No one knew these monsters’ destination, but whenever people looked out their windows, they saw the monsters parading through the night streets, like a festival procession.

Despite being called monsters, these creatures were not frightening upon closer inspection. In fact, they were quite endearing. They resembled creatures that have evolved incorrectly, forming a society of monsters: there were cape-wearing birds with the webbed feet of frogs, octopuses with eight eyes, elderly elephants reduced to skeletons, and sorrowful fly agarics crying red tears. Perhaps, these creatures were once ordinary animals, but for some reason – be it imminent death or isolation from peers – they ended up in Monster Park, evolving over time into their current forms.

Another storyline follows three children who have been barred from going out because of the nocturnal monsters. Bored, they resorted to everyday objects to entertain themselves, imagining cardboard boxes as adventure buses and bathtubs as spaceships and submarines. There seemed to be no grown-ups in this story. Each day, the children weaved fantasies out of the ordinary – such as imagining the caress of sunshine and breeze on their skin – in the company of their tuxedo cat.

In their imaginary underwater world, the children encountered lost monsters. To help them return home, the kids remodeled their submarine to accommodate the monsters and set off for Monster Park. junaida did not illustrate this journey; we only see the children sleeping, surrounded by circus toys reminiscent of Monster Park.

In the morning, the children stood on the empty streets, the monsters having departed. The final drawing shows Monster Park moving slowly through the forest towards distant mountains. Is this the scene after the children had sent the monsters home? I can’t help but imagine that after returning the monsters, the children were invited into Monster Park, where they enjoyed a strange yet delightful afternoon tea at a round wooden table lined with a white cloth.

The metaphor for the pandemic is hard to miss, but reading the story that way feels dull. I would rather believe it all truly happened.

Closing the picture book, I took a sip of Guinness. At that moment, I was in an Irish pub called The World End, in Ueno. Post-pandemic, the city streets were once again crowded with people hurrying to their destinations. I imagined that somewhere out there, in an unseen distant place, Monster Park was clumsily making its way forward, with the sound of metal clinking.