Born in the 1980s, I had had in my possession a few pen cases before in my childhood. Back then, among the most popular pen case designs for students include those iron pen cases decorated with cartoon illustrations as well as plastic ones containing plenty of small compartments. During my secondary school years, both pens and other stationery items are put together into pen bags with a huge capacity, and since then, pen cases have faded away from my life. But recently, I have stumbled upon this wooden pen case with black lacquer finish. The landscape painted on its surface has faded beyond recognition, which inspires immense curiosity in me.

漆液來自漆樹,從漆樹上剛採割並處理過的樹脂稱為「生漆」,經過加熱處理的「生漆」便是「熟漆」。無論是「生漆」或「熟漆」,兩者都是漆器製作中常用的漆料,「漆器」則泛指外表覆蓋著漆的容器,漆層能為木製或竹製的容器帶來防潮、耐熱和耐磨等保護性作用。日本人早於公元前四百年便開始製作漆器,它在日本的傳統飲食文化或花道、茶道等傳統生活習俗上有著相當重要的位置。

Lacquer comes from lacquer trees, and the sap tapped from the trees and processed is called “raw lacquer”, which further becomes “processed lacquer” after being heat-treated. Both raw lacquer and processed lacquer are the most commonly used materials for finishing in lacquerware. Lacquerware refers in general to containers covered with lacquer on their surface. The layer of lacquer can serve to protect wooden or bamboo containers against humidity, heat and abrasion. Since as early as 400 BC, the Japanese already started making lacquerware, which has played a key role in the traditional lifestyle and customs in Japan as reflected in its traditional food culture, Kadoh, the art of flower arrangement, or Chado, tea ceremony.

After going through two thousand years in the current of history, the Japanese has cultivated the finest lacquerware craftsmanship, and their unrivalled patience and attention to detail explain why it has captured the imagination of the people of the world. Exquisite Japanese lacquerware boast a surface as shiny and smooth as a mirror without even a tiny flaw. A piece of lacquerware of the finest quality can take as much as a decade to make, involving complicated procedures and all-out physical and mental effort. In Japanese, there is a saying that goes “urushi (lacquer) should be applied in a boat at sea”, which encapsulates its stringent standard of not tolerating even a tiny bit of dust on the lacquer lay.

In the later years, Japanese lacquerware gradually gained popularity in the West. People from the UK, France and Italy alike are fascinated with Japanese’s lacquerware craftsmanship, thereby catapulting Japanese lacquerware into the top on the list of collectables among the upper-class in the western world. In the late 17th century, a saying went around alleging that the Japanese detested the idea of exporting the best lacquerware to the West, and they believed that the best must be kept within the country. As a result, the demand for Japanese lacquerware exceeded its supply, and the craze for Japanese lacquerware not only did not die down, but became even more intense. Italy took the lead and became the first western country to produce lacquerware. The production, in truth, amounts to an imitation, as close as possible, of the Japanese way of making lacquerware, including containers and household products.

This has led to the birth of the term “Japanning”, a noun with an ironic overtone which refers to the “imitation of Japanese lacquerware” by western countries. Eyeing potential profits, other western countries also rushed to set up “Japanese” lacquerware factories, bringing oriental-style lacquerware to the life of the rich. When a culture of a country crosses the ocean on a long journey to the other side of the world, its most precious essence will all be lost on the way. What remains, sadly, is no more than the fragile outer surface. Despite Westerners’ best efforts to learn Japan’s lacquerware craft, their thinking and lifestyle, after all, were too different from the Japanese’s. As a result, “Japanning” lacquerware became somewhat formalistic, giving the feeling that it has the material form but lacks concrete substance.

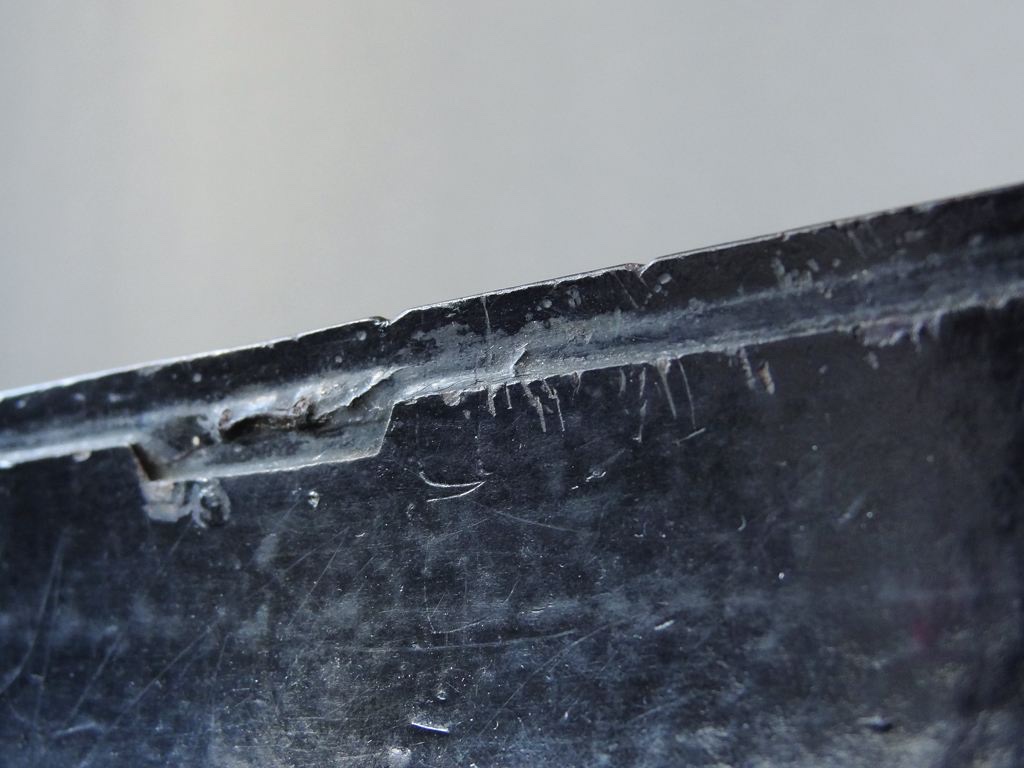

Nevertheless, Japanese lacquerware at last witnessed a rise to popularity and prominence in the West. In fact, this “Japanese” pen case I have with me is actually one of the lacquerware designed by the French in the early 20th century. Historically speaking, it is an imitation, but in my opinion, it is not completely a good-for-nothing. Quite the contrary, it actually boasts qualities worthy of admiration. First of all, after almost one hundred years in existence (including the unfortunate circumstances of the previous owner), despite having chipped corners here and there, the wooden case remains firm and intact, which testifies to the fine quality of the wood. Furthermore, the surface of the case, being slightly curved, fits in perfectly with its body, which speaks to top-class craftsmanship.

I used to have an impression of lacquerware being glossy and delicate, and showcasing an attention to details that is at times excessive. Such an excessive pursuit of perfection in the craft creates a divide between the object and the person, making it difficult to blend it in with life. Apparently, this pen case was not made with black lacquer of the best quality. After many years of usage, the lacquer surface has lost its luster and is already covered with scratches and dents. Hand-drawn landscape on its surface has faded in color, transforming itself into an unintelligible collage of broken pieces. Lacquer on the edges has also been damaged, exposing the wooden surface underneath – all of these tell the story of its life as a competent pen case. What is stored inside the case is certainly not only stationery, but also memories.